By Jacques Tchamkerten

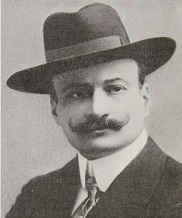

Camille Erlanger belongs to the “belle époque” of opera composers such as Alfred Bruneau, Xavier Leroux, Georges Hüe and Henry Février. They all knew the ins and outs of writing for the theater, and dramatic music was a major part of their catalog. Yet none of them made a lasting impression on the operatic landscape of their time, even though the quality of their music deserves to occupy a significant place in the theater repertoire.

The Erlanger family name is shared by many Jewish families of German and Alsatian origin. It is common to many unrelated musicians: composers Jules and Gustav Erlanger and Frédéric d’Erlanger (1868-1943), whose career took

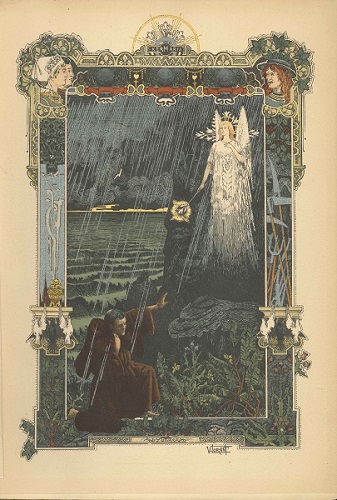

At first glance, Camille Erlanger was not predisposed to a musical career. His parents, who had left their native Alsace for Paris, were modest shopkeepers far removed from the artistic world. Born on May 24, 1863, the child showed an obvious aptitude for music. He entered the Conservatoire in 1881, and was admitted to Léo Delibes’ composition class in 1886. In 1888, ahead of Paul Dukas, he won the Premier Grand Prix de Rome with his cantata Velléda. In 1895, his lyric legend Saint-Julien l’Hospitalier, based on Flaubert’s tale of the same name, made a great impression with its scope and harmonic boldness, reflecting his Wagnerian fervor.

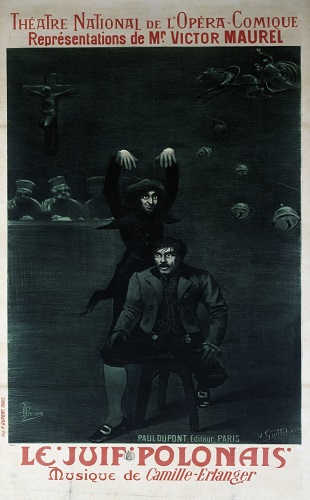

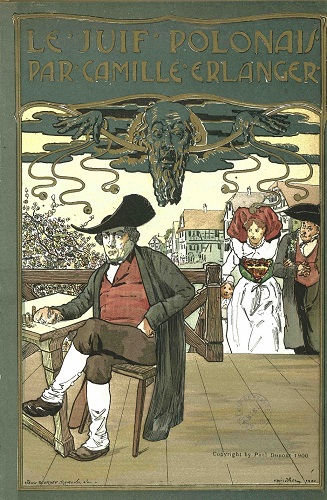

Camille Erlanger’s first opera, Kermaria, combines fantasy and legend in a Breton setting. Premiered at the Opéra-Comique in 1897, it was only a mediocre success. The composer was happier with Le Juif polonais, based on a novel by Erckmann-Chatrian. This dark drama of guilt and remorse, set in an Alsatian village, is in keeping with the naturalist esthetic represented at the time by composers such as Alfred Bruneau and Gustave Charpentier. Performed with great success at the Opéra-Comique in 1900, Le Juif polonais was revived fairly regularly until the late 1930s.

It was undoubtedly through his mentor Léo Delibes that Erlanger was introduced to the salon of Isaac de Camondo, banker, diplomat, eminent art collector and amateur composer whose opera Le Clown was performed at the Opéra Comique in 1906. In 1902, he married one of the latter’s second cousins, Irène Hillel-Manoach (1878-1920), whose initiatory novel Voyage en kaleidoscope became a classic of esoteric literature and attracted the interest of the Surrealists. Their son, Philippe Erlanger (1903-1987), a senior civil servant, writer and art critic, was one of the founders of the Cannes Film Festival.

At the same time as Le Fils de l’Etoile, the musician composed the work that was to be his greatest success: Aphrodite, whose libretto by Louis de Grammont adapts Pierre Louÿs’ famous novel for the stage. The erotic charge of the argument, the splendor of the staging at the Opéra-Comique premiere in 1906 and the presence of Mary Garden in the role of Chrysis all played their part in the work’s great success. But Erlanger’s music, with its innate sense of sound design, its highly personal treatment of conductive motifs and the often unexpected physiognomy of its melodic patterns, was just as important to the success of a work whose musicologist Leslie Wright rightly said that “its hybrid character is perhaps more revealing of the beginnings of modernism than other more linear scores”.

In 1909, Erlanger staged Bacchus Triomphant, a large-scale popular spectacle, in Bordeaux, followed by L’Aube Rouge, a drama set in Russian anarchist circles, in Rouen in 1911.

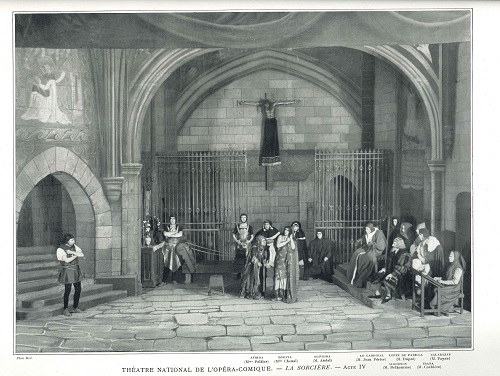

His next two works were composed simultaneously: Hannele Mattern, and La Sorcière, a musical drama in 4 acts based on a drama by Victorien Sardou. The action, tragic and violent, narrates the love affair between a captain of the Toledo archers and a Muslim woman with supernatural powers, who chooses suicide to escape the pyres of the Inquisition. Despite its success, the 1912 premiere at the Opéra-Comique met with mixed reactions: the frightening depiction of the Church was badly received by some critics, whose comments were accompanied by undisguised anti-Semitic relents. The work features soprano Marthe Chenal in the lead role. A veritable “sacred monster”, she was Erlanger’s first choice for Bacchus triomphant, L’Aube rouge and, above all, this Sorcière, whose fullness of voice and stage presence made a great impression.

La Sorcière was Erlanger’s last operatic work created during his lifetime; at his death, he left two operas unfinished.

A rare transposition of a film to opera, Forfaiture, first performed in 1921, shocked audiences with its passionate violence and crude libretto. Faublas, however, never saw the limelight, and the score, completed by Paul Bastide, rests in the reserves of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Although Camille Erlanger established himself above all as a lyric composer, his catalog includes numerous melodies, a few piano and symphonic pages, as well as music for La Suprême Epopée, a patriotic propaganda film by Henri Desfontaines, produced by the Service photographique et cinématographique des Armées in 1919.

Erlanger’s musical style is characterized by dense writing, abundant conductive motifs and opulent orchestration. His harmonic language does not shy away from sometimes surprising audacities that can lead briefly to the frontiers of tonality. An outstanding orchestrator, he possesses an obvious gift for musical scenery, and knows how to set it in a striking manner in just a few measures. Lyrical outpourings and voluptuous melodic outbursts are rarely part of his vocabulary. His qualities as a dramatist crystallize around his remarkable sense of sound design. Through the singularity of a melodic design or harmonic sequence, he succeeds in creating a remarkably effective musical framework, with an evocative force that enables him to characterize his figures, their personalities and their states of mind. At the time, this highly theatrical yet unconventional approach seems to have disconcerted both lovers of traditional lyric art rooted in the Gounod-Massenet tradition, and those who championed the “new art” of opera represented by composers such as Debussy, d’Indy and Dukas.