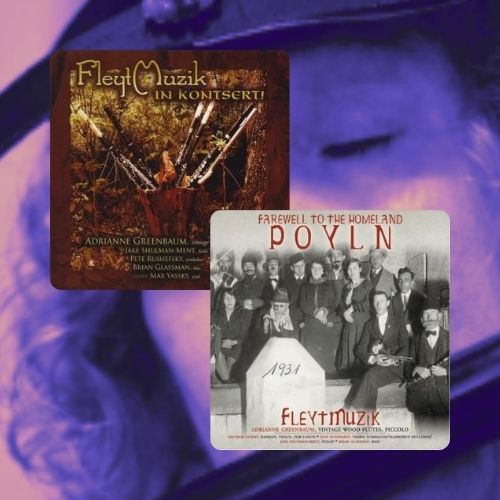

ARC Ensemble

Chandos Records Ltd – Collection Music in Exile

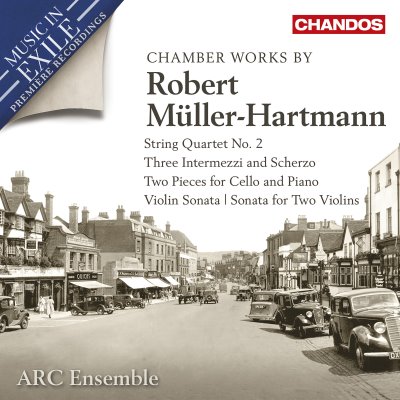

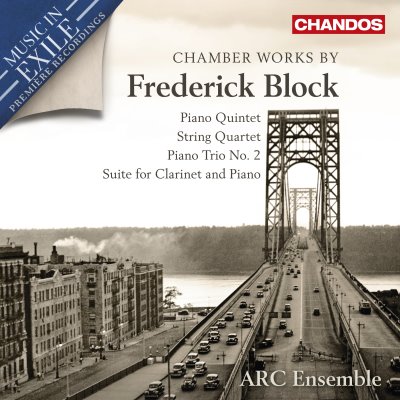

The seventh and eighth CDs in the Music in Exile series, Chamber Music by Robert Müller-Hartmann and Chamber Music by Frederick Block, released by Chandos in 2023 and 2024 respectively, introduce us to the unjustly forgotten works of these two Jewish composers, German and Austrian, who emigrated to England and the USA in the 1930s to escape Nazism.

Robert Müller-Hartmann (1884-1950) is one of a long list of European Jewish composers marginalised and forgotten following the advent of Nazism and the societal upheavals that followed the Second World War.

The fate of this composer, teacher and musicologist is described at length in the booklet of this well-documented disc by Simon Wynberg, director of the Canadian-based Ensemble ARC (Artists of The Royal Conservatory), founded in 2002.

Born in Hamburg on 11 October 1884, Robert Müller-Hartmann was the son of clarinettist and piano teacher Josef Müller and his wife Jenny (born Hartmann). He was the great-cousin of composer and conductor Paul Dessau (1894-1979). From 1900 to 1904, he studied composition at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin with Eduard Behm, a disciple of Brahms, and counterpoint with the composer and critic Max Loewengard. In 1912, Müller-Hartmann married Rebecca Elisabeth Asch (1890 – 1981) – known as Lisbeth – the daughter of a prominent Jewish family in Hamburg. Hamburg was to remain the centre of the composer’s professional and family life. Müller-Hartmann taught music theory at the Krüss-Färber Conservatory and the Bernuth Conservatory and, from 1923, harmony and composition at Hamburg University. He also wrote essays and reviews for a number of music magazines and sat on the music advisory board of the Nordische Rundfunk Aktiengesellschaft (North German Broadcasting Corporation).

Several important conductors played his works: Karl Muck, Carl Schuricht, Richard Strauss, who conducted his Symphonic Overture, op. 7, in Berlin in 1917, and Otto Klemperer, a former student of the Stern Conservatory, who premiered his Leonce und Lena Overture, op. 14. German radio stations, notably Nordische Rundfunk, regularly broadcast Müller-Hartmann’s music.

Dismissed from his post at Hamburg University in 1933, he taught at a Jewish girls’ school before fleeing to England in 1937. He settled with his wife and his three children in Dorking, about 25 miles south of London. Through his daughter, he met the British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, with whom he became friends and collaborated. Towards the end of the summer of 1940, Müller-Hartmann was interned on the Isle of Man as a German national. He was released a few weeks later thanks to the support of Vaughan Williams. But he had to wait another three years before being officially granted permission to teach music by the Home Office. During the war, the BBC broadcast very few works by German or Austrian composers, even if they were Jewish and refugees. The general antipathy towards exiled German musicians and Müller-Hartmann’s modest, rather self-effacing personality meant that he was soon forgotten, all the more so when he died prematurely of a cerebral haemorrhage on 15 December 1950.

It is worth noting, however, that the BBC unexpectedly presented a selection of Müller-Hartmann’s lieder in the summer of 1945. In Israel, thanks to the promotion of his son Jedidja, his Sonata for Two Violins, op. 32, and his Sinfonietta were broadcast on Kol Yerushalayim.

After his death, his musical manuscripts were sent to his sons in Israel, who donated them to the Academy of Music and Dance in Jerusalem. They remained largely untouched until the release of this CD, thanks to the remarkable work of Simon Wynberg.

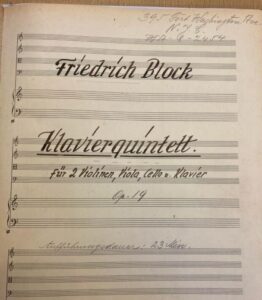

His first teacher was the Czech composer Josef Bohuslav Foerster, followed by Hans Gál at the University of Vienna. Conservative by nature, Block’s music met with modest success in the 1920s. In Vienna on 15 January 1922, a concert devoted entirely to his music included a String Quartet in A minor, a group of Lieder and a Piano Quintet in G major. Other performances of his works followed in Vienna and Prague. In the early 1930s, Block’s music featured in programmes promoting the music of younger Austrian composers. Many of them, such as Karl Weigl, Erich Zeisl, Ernst Kanitz, Otto Jokl and Walter Bricht, were Jewish and sought refuge in the United States. During the 1930s, Block also devoted himself to opera, and in a burst of extraordinary energy composed six in the space of four years. The third, Samum, premiered in January 1936 at the Slovak National Theatre in Presburg (now Bratislava) to great acclaim.

As German forces gathered on the Austrian border and the country showed its enthusiasm for union with Germany, Block realised the imminent threat to Austrian Jews. In March 1938, after Hitler’s annexation of Austria, Block obtained a British visa in Trieste, then flew from Zurich to London where he met up with his fiancée, Ina Margulies, whom he married in the Richmond District Synagogue on 15 August 1939. They lived at Kew for the last few months of their stay in London, where Block completed his opera Schattenspiel (Game of Shadows). Their departure for America was delayed until their immigration application was approved the following May. On 11 June 1940 they boarded the Britannic, a Cunard-White Star Line transatlantic liner, and left Liverpool for New York, arriving in the summer of 1940.

There he found work composing and arranging scores for radio orchestras – mainly CBS – and arranging orchestral works for publication in solo piano versions. But in addition to these time-consuming activities, he composed an enormous amount of chamber music. Hypersensitive, stressed and haunted by premonitions of imminent death, Frederick Block rarely left his flat in Washington Heights. His friend and colleague Otto Janowitz wrote: ‘He was a composer who did not belong to any school or movement, who did not want to prove anything through his composition, who was neither abstract nor romantic, but who, with tireless perseverance, completed work after work without worrying about criticism, success or, unfortunately, even performances, simply following honestly his desire to create’.

Early in 1945, he was diagnosed with cancer. Radiation proved ineffective, and on 1 June, just three months before his forty-sixth birthday (and American citizenship), Frederick Block died. He was buried in Cedar Park Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey. Ina Block never remarried and outlived her husband by fifty-five years, disappearing in 2000. Her grave is next to Frederick’s.

In 2001, the New York Public Library acquired the des Frederick Block archives from the estate of his widow, Ina Block, and Simon Wynberg discovered them by chance in the library’s collections. He was moved by the story of this composer, by the beauty of his works and by the almost total anonymity that followed his death. He then began a research project that culminated in the publication of this deeply moving CD which, like the previous opuses, pays tribute to the musicians of exile whose works have unjustly fallen into oblivion.

Two discs you really must discover…

Order the CDs Music in Exile

More about the ARC Ensemble