by Hervé Roten

The Jewish liturgy is full of surprises! In 1993, while I was coordinating the activities of the Yuval Association for the preservation of Jewish musical traditions, under the direction of the musicologist Israel Adler, I was contacted by the producer of France Culture, Marie-Dominique Arrighi, who was preparing a series of radio programs on the theme of integration and the acquisition of French nationality[1]The four weekly Nuits magnétiques programs by Marie-Dominique Arrighi on the theme of “Becoming French” were broadcast on France Culture from April 20, 1993..

During an interview with Professor Ady Steg, President of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, the latter had told her that the emancipation of Eastern European Jews had been achieved thanks to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic conquests. The Orthodox and Hasidic Jews, then free to express their faith outside the ghettos, would have paid tribute to their liberators by using the music of the Marseillaise to sing some of their prayers.

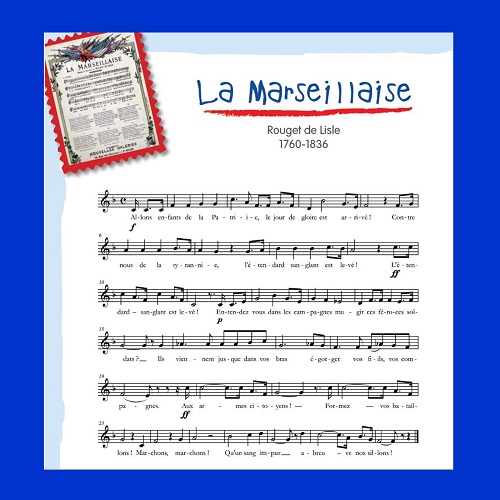

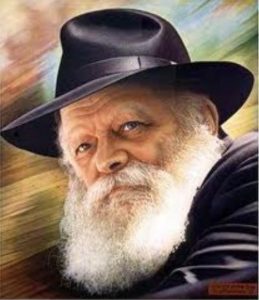

Although there are several Napoleonic marches in Hasidic music, I had never encountered a tune as emblematic as the Marseillaise before. After an investigation in the Paris Lubavitch circles, it appeared that a Shabbat morning piyyut, Haaderet vehaemuna, was indeed sung to the first part of the Marseillaise melody! Intrigued by this unorthodox borrowing, I asked my informant about the origin of this tune. According to him, its introduction in the liturgy was relatively recent, but he could not give me more details.

I then contacted the Jerusalem Lubavitch community through Israel Adler, Yaakov Mazor and Gila Flam, the current director of the Israel National Sound Archives. After a short investigation, they were able to obtain the following explanations. In 1973, when the Habad movement was still not very widespread in France, a hundred or so French Jews went to the Rebbe of Lubavitch in New York for the High Holidays.

Audio 1: The Marseillaise sung by the Lubavitch. Excerpt from the program Nuits magnétiques by Marie-Dominique Arrighi broadcast on France Culture on April 20, 1993

Thus, since 1973, the piyyut Haaderet vehaemuna has been sung on Saturday mornings and holidays to the tune of the Marseillaise. The Rebbe later justified his decision by pointing out that the Lubavitcher hymn Ufarazta (You shall spread; Genesis 28:14) corresponded closely to the anagram of the word Tsarfat, which means “France” in Hebrew. These two terms were thus in deep and harmonious relationship. Moreover, according to the Gematria (a numerological process for interpreting Hebrew texts), the total of their letters is 770… a number that corresponds to the number of the Rebbe’s house in New York (770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn)!

Audio 2: Ufarazta, Hymn of the Lubavitch

To hear the Lubavitch sing the Marseillaise in Hebrew is a paradox, particularly since the founder of the Habad movement, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Lyadi (1745-1813) – spiritual grandson of the Baal Shem Tov – had deliberately sided with the Russians against the Napoleonic invasions, which he considered dangerous for Orthodox Judaism. On the other hand, the warlike lyrics of this hymn did not really predispose it to accompany the singing of a prayer. But for the Hasidim, every melody, whether it be the most impure or the most banal, contains a divine spark that can be released by the devequt[2]A statement of total adherence to God in all acts of daily life..

This investigation into the use of the Marseillaise melody in prayers revealed the existence of a second recording from the island of Djerba (Tunisia). Following a visit by French officials to the island, the Jewish community honored their hosts by singing their national anthem. The tune was then remembered and served as the musical basis for a piyyut that is still sung today at services. The oriental intonation has been interwoven with the original tune, which gives this Marseillaise an original and surprising aspect.

Audio 3: Djerbian Piyyout sung in Arabic to the tune of La Marseillaise

Finally, recently, my friend Joël Rochard, President of the Cercle Bernard Lazare (Paris), sent me an e-mail entitled Rouget de Lisle au secours d’Ibn Gabirol. He explained that “his grandson Samuel, 11 years old, was struggling to learn the Adon Olam prayer. I explained to him that this liturgical poem can be sung to various melodies. Everyone can choose the tune they want.

I suggested the Marseillaise. He liked the idea.

An hour later he knew Adon Olam by heart.

I must admit that I tried to do the same. It works perfectly!

Consult other documents on the Marseillaise in our collections