By Francesco Spagnolo (University of California, Berkeley)

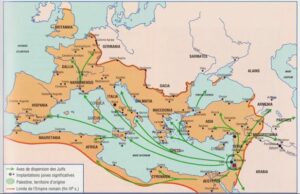

The history of Jewish music in Italy is long, fascinating, and filled with contradictions. Length is due to the very history of Italian Jewry, whose origins go back more than 2,000 years. Fascination stems from the global meeting of the music of the Jewish Diasporas in the early-modern period, an unprecedented interaction among distinct Italian, Ashkenazi, and Sephardic traditions with Italian musical culture and its innumerable cultural, regional, and linguistic differences. The contradictions concern the many identities, visible and invisible, of the Jews of Italy: the secrecy of ghettos, places of exclusion, and also of explosive musical ferments emblematically represented in the works of Salamone Rossi (ca. 1570-1630, active in Mantua at the Gonzaga court); the conflicts and the hidden consonances between Judaism and Christianity, and the distance between the liturgy of the Church and that of the synagogue, at once brief and unattainable; the integration, and the cultural symbiosis, of Jews and Italy, a shared feeling so beautifully expressed in Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco (1842), a biblical parable of exile, emancipation, and national unification; and, finally, the tragic character of the Fascist parable, which ended in the Holocaust, and the destruction of Italian synagogue life. But the main contradiction that characterizes Jewish music in Italy is that, despite its undisputable richness, it is a phenomenon still relatively obscure to the scholars of Judaism. Musicologists and cultural historians often know very little about the musical traditions of the Italian Jews, and struggle to grasp a cultural landscape made of Chinese box-like specificities, in which Judaism and italianità (“Italian-ness”) blend seamlessly.

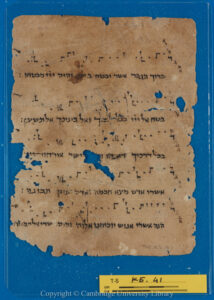

Musical sources documenting the development of Jewish liturgical music in Italy prior to the 19th century are rare, precious, and extremely fragmentary. Indeed, the earliest known Jewish musical source – the manuscript notations produced in the 12th century by Johannes, or Obadiah “the Norman Proselyte,” a native of Oppido Lucano (Fragment Cambridge TS. K 5/41 and Fragment Cincinnati ENA 4096b) – stems from Italy, and so do many a musical transcription (often focusing on the oral traditions for chanting the Torah) by Christian humanists from the 16th century onwards, such as those published by Giulio Bartolocci (1613–1687) in Bibliotheca magna Rabbinica (volume 4, 1693).

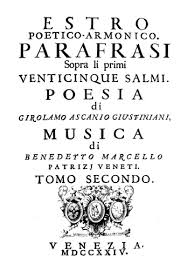

These fragments were followed in the 17th and 18th centuries by full-fledged compositions for the synagogue by Jewish (Salamone Rossi, hashirim asher li-shelomoh, Venice 1622-23) and non-Jewish (Carlo Grossi, Cantata hebraica in dialogo, Modena or Venice, before 1682; and Christian Joseph Lidarti, Oratorio Ester, 1774) composers, or by Jewish and non-Jewish musical collaborators working closely together. Among the latter are the transcriptions of 11 synagogue songs from the oral traditions of Venice, published by Benedetto Marcello (1686-1739) in his collection, Estro poetico-armonico: Parafrasi sopra li salmi (Venice, 1724–1727); three extant

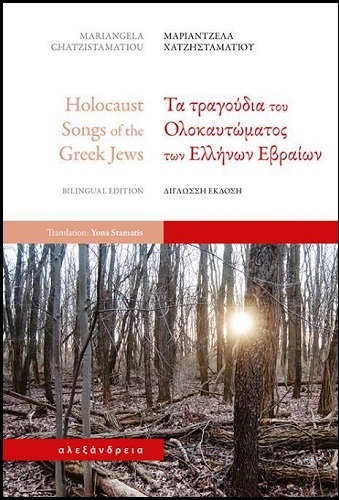

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the role of music in Italian Jewish evolved in many directions, bridging a host of diverse musical worlds, including liturgical, art, and popular music, and spanning from the intimate sphere of the synagogue to the realm of public performance. In this period of time, Italian Jews were confronted with a number of challenges: the transition from segregation in the ghettos to social and political Emancipation; the formation of a new national identity during the Risorgimento; urbanization and the eclipse of the many small communities that for centuries had animated the Italian Jewish experience; the anti-Semitic legislations and persecutions during the Second World War; the reconstruction of Jewish communal life after the Holocaust, the immigration of Jewish groups from North Africa and the Middle East following the creation of the State of Israel; and, by the end of the 20th century, the emergence of a “virtual Jewish culture” through increased participation of non-Jews in the creation of cultural (especially musical) products that mainstream culture views as Jewish.

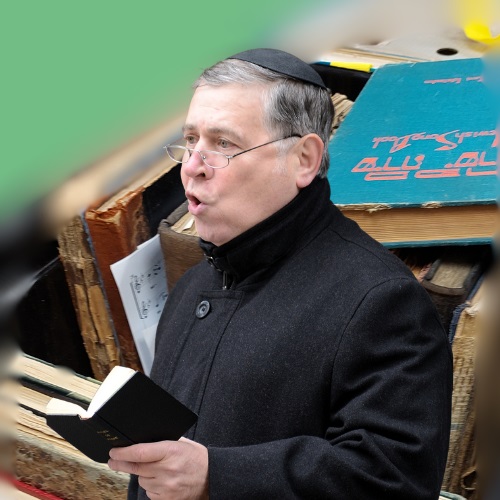

In the 19th century, music composition increased dramatically, and virtually every Italian congregation commissioned and collected tens of new polyphonic compositions specifically devoted to synagogue worship.

These musical manuscripts represent a synagogue sound reminiscent of several non-Jewish musical worlds: arias and recitatives evoking Opera (and operetta); the liturgy of the Catholic Church; and the revolutionary hymns of the Risorgimento: all sung by small choirs of children and adults (at times also including women), and accompanied by the organ or, depending on the space and the resources made available by each synagogue, by the harmonium. The names of the composers, and often of the performers, appear together with the scores.

Among them were local Jewish amateurs, whose desire to write and perform music was often accompanied by monetary donations to the community; Jewish professionals (Michele Bolaffi and David Garzia in Livorno; Bonaiut Treves and Ezechiello Levi in Vercelli; Giacomo Levi in Florence and Turin; Settimio Scazzocchio, Saul Di Capua and

Musical composition for the synagogue continued well into the 20th century, when female and mixed-gendered synagogue choirs became increasingly more popular, but came to an almost complete halt after WW2, when choirs and organs were progressively abandoned, with the notable exception of Rome, where synagogue choral music and composition continue to thrive to this day.

More about Italian Jewish Music