by Jorge Rozemblum

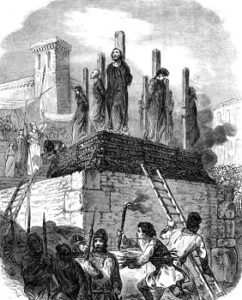

As we know, the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, although it is clear that many remained after converting to Catholicism and that some of them continued to practice their faith in secret. We have neither the scores nor sufficient documentation on the music of the Jews during their presence in the Iberian Peninsula, which lasted almost a thousand years: only complaints from some rabbis about the incorporation of melodies from other religious communities (Muslim or Christian) into the devotional songs (piyyutim) that were usually part of the liturgy. During their long  absence (or clandestinity), we can find some evidence of the persistence of Spanish Judaism in the accounts of other communities. For example, although the gypsies began to arrive in Spain during the period when the Jews were leaving, a bulería por soleá[1]Bulería for Soleá: Flamenco dance of intermediate rhythm between the “Soleá” and the “Bulería” has remained engraved in the flamenco heritage that makes one shudder because it alludes to the Inquisition’s auto-dafés: “You are like the Jews, you are like the Jews; even if they burn the clothes on your body, do not deny what you have been”[2]Lyrics in Spanish : “Como los judíos tú eres, tú eres como los judíos; aunque te quemen la ropa puesta en el cuerpo, no reniegas de lo que has sío”.

absence (or clandestinity), we can find some evidence of the persistence of Spanish Judaism in the accounts of other communities. For example, although the gypsies began to arrive in Spain during the period when the Jews were leaving, a bulería por soleá[1]Bulería for Soleá: Flamenco dance of intermediate rhythm between the “Soleá” and the “Bulería” has remained engraved in the flamenco heritage that makes one shudder because it alludes to the Inquisition’s auto-dafés: “You are like the Jews, you are like the Jews; even if they burn the clothes on your body, do not deny what you have been”[2]Lyrics in Spanish : “Como los judíos tú eres, tú eres como los judíos; aunque te quemen la ropa puesta en el cuerpo, no reniegas de lo que has sío”.

From the middle of the 19th century (after the fourth and final abolition of the Inquisition), the Jews returned to Spain in small numbers, most of them from central Europe and who were involved to modern industries such as the railways. But it was in Melilla that a Jewish community of North African Sephardic origin began to settle, bringing with it its rituals and melodies, although these songs did not go beyond the synagogues and the family. One of the first to explore this unknown field was Arcadio de Larrea Palacín (1907-1985), a flamenco musicologist, folklorist and member of the Real Academia de la Lengua (Royal Academy of Language), who visited Melilla and Ceuta, as well as the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco, where he noted several popular melodies. However, his work did not go beyond the academic framework.

At the beginning of the 20th century, and especially thanks to the work of Senator Ángel Pulido (1852 – 1932), an emerging feeling of philosemitism developed that led in 1924 to the promulgation of a list of names of Sephardic Jews of Spanish origin that allowed them to obtain Spanish nationality. In 1936, the onset of the Civil War and the triumph of the nationalist camp (supported militarily by anti-Semitic regimes such as the Nazis) broke this momentum of rapprochement for decades. However, during the Second World War, several Jews seeking refuge arrived in Spain, such as the Belgian soprano and musicologist Sophie Heyman (1915 – 2011), daughter of a Sephardic and an Ashkenazi (Jewish from Eastern Europe), who changed her name to Sofía Noel. The presence and talent of the latter inspired the creation of scores claiming the Judeo-Spanish past, signed by composers like Fernando Obradors. The soprano Sofía Noel was accompanied on the piano by Ricardo Viñes, who trained in Paris the Sephardic pianist Victoria Kamhi (born in Istanbul in 1902 and died in 1997), who married the composer Joaquín Rodrigo (known mainly for his Concierto de Aranjuez).

After the end of the Protectorate, the independence of Morocco and, especially, the wave of anti-Semitism following the Six Day War in Israel in 1967, many Sephardic Jews from the north of Morocco emigrated to the large Spanish cities (mainly Madrid and Barcelona), bringing with them their religious rites and music, which were practiced mainly in the synagogue and family setting. That same year (1967), the folklorist and musician Joaquín Díaz González toured the United States giving recitals and lectures at universities. He met the founder of the Folkways Records label (Moses Asch), who gave him the record of Sephardic folk songs that he had published in 1959. This record, performed by Gloria Levy, revealed to him an unknown repertoire and language, although strongly linked to his own heritage, which he quickly absorbed. His first records inspired by this tradition (even though they are performed with a pronounced Hispanic character) created the basis for what in Spain is considered, until today, Sephardic music. At the same time, the Israeli musicologist Itzhak (Isaac) Levy (father of the singer Yasmin Levy), born in Manisa (now in Turkey) in 1919 and deceased in 1977, published two important collections of Sephardic music, including both popular Judeo-Spanish music and liturgical songs in Hebrew, which served as references for singers from Spain – and other countries – to approach this repertoire.

Barminan – Joaqin Díaz

These events marked the beginning of the career of singers and groups sometimes entirely dedicated to the Sephardic repertoire. Other artists integrated Judeo-Spanish song into their repertoire along with popular Spanish music. At the same time, an interest in Sephardic music of liturgical and paraliturgical origin in Hebrew began to develop, making repeated use of contrafacta, that is, the substitution of one text for another in vocal music, while preserving the melody. This mechanism reinforced the ideal of a “music of the Three Cultures”, alluding to the supposed coexistence and tolerance between the three monotheistic religions (Christians, Muslims and Jews) in medieval Spain.

Quando Veyi Hija Hermoza – Gloria Levy

As for Jewish music from the non-Hispanic tradition, its impact was less. For example, klezmer music (from the instrumental tradition of East European Jews) is best known among non-Spanish and non-Jewish groups – such as the Polish band Kroke – despite the emergence of a few national initiatives in recent decades, such as the group Klezmer Sefardí (Sephardic Klezmer), which involves musicians from all backgrounds and religions. Other aspects of Jewish music (from the Middle East, for example) are virtually absent from the peninsular scene.

Sun – Kroke (Extract)

Miserlou – Klezmer Sefardi (Extract)

The small percentage of Jews in the Spanish population (about 0.1%) reduces the artistic possibilities of those who today would like to dedicate themselves to some form of Jewish musical expression. Nevertheless, we can find important Jewish names in popular musical genres such as Jorge Drexler, Ariel Rot, Alejo Stivel or Federico Lechner, as well as some representativeness among the performers of classical music, although the most famous national representatives of music identified as Jewish do not belong to the said community.

Jorge Rozemblum, Director of Radio Sefarad and Spanish correspondent of the European network of Jewish music