By Hervé Roten

Chasidism, the mystic Jewish movement born in Eastern Europe in the middle of the 18th century, enabled the emergence of a lot of music aimed to transcend the impurities of this world… …

In the middle of the 18th century, the misery and persecutions suffered by the Jews in Eastern Europe led them into a deep withdrawal. Following the disillusionment born from the apostasy of the false messiah Sabbataï Tsevi, many Jews yielded to a surrounding mysticism leading to the emergence of the chasidic movement.

Chasidism was created in Podolia by Israël ben Eliezer Baal Shem Tov (1700-1760). Regarded at the outset as a reaction to the bleak intellectualism of rabbis, this popular movement preached the accession to the divine by joy (simcha) and enthusiasm (hitlavout) in prayer. To this doctrine, inspired by the kabbalistic movement of Safed, one can add the concept of deveqout (“attachment”) which marks a state of total adherence to God in all the daily activities of life. Thus the chasid serves his creator even when he eats or drinks, provided it is done in a spirit of holiness.

Although it was opposed by the official authorities of the Jewish community (the mitnagdim), the chasidic movement grew quickly: we believe it had conquered over half of the Eastern Jewish population at the beginning of the 19th century. At the head of the chasidim “rules” a tsadik who holds a real court. The role of a tsadik, passed on first from the master to the most prestigious of his disciples, became progressively hereditary, to the point that it created dynastic lineages. Each dynasty – generally named like the town where the ancestors established their court – developed original traditions; however, all of them kept the usage of the Yiddish language and of several common practices. Among them, one can find dancing and singing.

The Baal Shem Tov and his disciples considered music and dancing as a way to rise the soul above the world’s impurities. During Shabbat meals, they sung zemirot (domestic canticles) and often invented new melodies. Shortly after the Baal Shem Tov’s death, the creation and the singing of these nigunim (melodies, tunes) became an essential pillar of chasidic mysticism. In the chasidic approach, the nigun goes beyond language: it is able to express the unspeakable. A chasidic saying claims “silence is better than speech, but singing is better than silence”. For this reason, the nigun expresses all the human emotions. Meditative or exalted, sad or joyous, its singing goes with the swaying of the body, chest and arms; it is sometimes added by handclapping. These body movements, supported by a total involvement of the chasid in his melody, can lead the singer to a true state of trance.

The majority of these nigunim are without words. The text has little importance; generally written after the melody, it is often reduced to a simple word or short onomatopoeias such as “doy doy doy” or “Ya-ba-bam”. The essence of the nigun lies in fact in the kavanah (the intention) that emerges in the singer’s heart; whatever melody or text is used. Such a philosophy explains to a certain extent the borrowings of melodies from Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Hungary, Romania or Turkey that abound in this repertoire. One can also find tunes of Napoleonian marches, a proof of the great hope felt by the Jews after the entrance of the French troupes into Poland.

The chasidic musical repertoire is thus extremely multiple in styles. Based on the blending of Jewish and non-Jewish melodies, vocal and instrumental, metric and of free rhythms, it doesn’t show any unique characteristic. It is thus very hard to classify it. According to André Hajdu and Yaakov Mazor (1972, E.J. 7, 1424-1425), the chasidim, themselves, number three big categories of nigunim :

- Table tunes (tish nigunim). They used to be sung at the tsadik‘s table before or after the meals. They are quite long tunes, rather meditative, with free or metrical rhythms. Most of them don’t have any lyrics ; the rare texts used come for most of them from the Shabbat’s liturgy, and in particular the zemirot (canticles).

- Dance tunes. These tunes have generally a periodic and symmetric structure; they are often composed of a small number of melodic patterns (two or three in general) with simple variations. Approximately half of these nigunim include a short biblical or liturgical verse put on the melody in a more or less repetitive way.

- The instrumental music concern waltzes, marches or particular tunes like those performed during the Meron pilgrimage in Upper Galilee.

For more than two centuries, the different chasidic dynasties created and transmitted many nigunim. Some were written down; others were recorded in the beginning of the century. At the peak of the chasidic movement, instrumental ensembles, singers and composers of nigunim were continuously connected to the tsadikim‘s court. Chazanim (cantors) were hired to teach new melodies to the pilgrims who, on a holiday period, came in number to listen to the rabbis teachings. The Second World War and the murdering of East European Jews put an end to this world.

Today, the main chasidic movements are settled in USA and Israel. Their musical repertoire has greatly evolved: it became more standard and poorer because of its diffusion through the media (concerts, discs, radios, etc.) and because of the use of Western musical notation, became more standard.

Source : Hervé Roten, Musiques liturgiques juives – Parcours et escales

Listen to the playlist Chasidic music (First part)

Listen to the playlist Chasidic music (Second part)

Listen to the playlist Chasidic music (Third part)

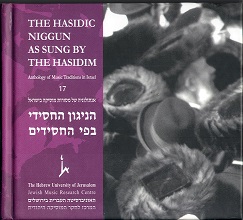

Purchase the CD The Hasidic Niggun as Sung by the Hasidim published by the JMRC