By Sylwia Jakubczyk-Ślęczka

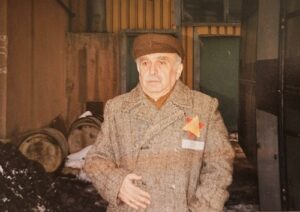

On 13 June 2024, Leopold Kleinman-Kozłowski’s music collection was donated to the Musicology Institute of the Jagiellonian University. It was gifted to the Library and Sound Library of the Musicology Institute by Marta Kozłowska-Woźniak, the daughter of the last klezmer of Galicia. This collection contains 621 documents, including numerous handwritten scores, song lyrics, and audio and video recordings.

Leopold Kleinman-Kozłowski was born on 26 November 1918, in Przemyślany, then a town of the Lvov district of the Second Polish Republic, today located in Ukraine. He was a grandson of Peysach Brandwein, the father of 14 children, 12 of whom were members of his klezmer ensemble. His most famous son was Naftule Brandwein, a clarinetist who became famous in America. However, it was Herman Kleinman, Leopold’s father, who suceeded Peysach Brandwein as the leader of the local klezmer band. As a violinist, Herman Kleinman was the leader of Przemyślany’s klezmer kapelye. He played with Sale Sekler (second violinist), Dudziu Brandwein (bass), Antschel Klarnetist (clarinetist), Shie Tsimbler (dulcimer player), and Hershele Dudlsack (drummer and dancer). Among the band’s members, only Herman Kleinman and Sale Sekler, Herman’s brother-in-law, could read music, while the rest had no formal music education. Everyone also worked in other professions: Herman and Sale were barbers, Antschel and Shie – tailors, only “Dudzio” Brandwein earned his living through music, running his own dance school in Przemyślany. The band’s rehearsals took place in Herman Kleinman‘s house, where young Leopold would listen in.

In his childhood, Leopold was enchanted by the sound of the dulcimer, so he took some lessons from Shie Tsimbler at his tailor shop. At the age of 6, he began his proper piano lessons. His first teacher was a Ukrainian woman from Przemyślany, Mrs. Hawronowa. The tuition took place at her home, which was probably the only place at that time where he could also practice playing the piano. He only got his own instrument in 1937, one year after his father’s return from the three-year economic emigration in Argentina. According to his autobiography, also in 1937, he started piano classes with Professor Tadeusz Majerski at the Polish Music Society Conservatoire in Lvov.

As a teenager he got to know all the different types of music around him. He had a chance to listen to the music of a Gypsy community which temporarily settled in his hometown. He used to wander to their camp instead of heading to school. Later, as a result of a short romance with a Ukrainian housekeeper, Leopold became interested in Ukrainian folk songs. He also enjoyed listening to the radio and the popular repertoire broadcast there. In the summer, he played it solo to people relaxing in the Galician meadows. He also used to play popular hits with his friends in the school band. In 1937, his father invited him to perform with his klezmer band at weddings. As an accordionist he was supposed to replace the dulcimer player, Shie Tsimbler, who had just retired. By then, he had some melodies written down on paper sheets. He also performed patriotic repertoire with his father and brother during official celebrations of Polish national holidays

Thanks to these musical pursuits, Leopold Kozłowski developed a good grasp of the music played at that time in Galicia, the region inhabited by a multiethnic, multireligious and multicultural society. Ironically, it seems that the traditional repertoire of his father’s kapelye was the one that aroused the least interest in this young man. But this is no surprise, as the Galician Jews of that period were not keen on it. Kozłowski recalled that ‘[wedding] guests came to Herman Kleinman asking him to play a particular tango or song broadcast by Radio Lvov! That was the real exam for the orchestra! They had to know everything, and if they didn’t, it was enough when the guest hummed a melody which the musicians immediately recognized, they adjusted the pitch and the music was ready to dance to’ (Cygan, p. 58). As Kozłowski explained, ‘at the beginning [of the wedding party] men and women (…) danced separately’ as traditionally required. However, ‘soon after, they were dancing together’ (Cygan, p. 58).

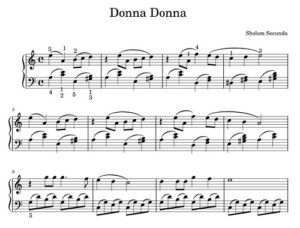

Describing the dance music that made up the traditional wedding repertoire on the eve of the Second World War, he mentions the titles of popular Yiddish songs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries: ‘Rozhinkes mit mandlen’, ‘Vu bistu geven?’ or ‘Di mizinke oysgegebn’ – played at theaters and composed by well-known authors like Abraham Goldfaden, Zusman Segalovich and Mark Warshawski. Thus, the “traditional” melodies listed by Kozłowski appear to have a contemporary character.

Why is that? As Walter Zev Feldman wrote in his article dedicated to prewar Galician klezmers, their popularity actually decreased as early as the beginning of the 20th century. The interwar period was just a swan song for klezmer bands. They were then replaced by modern Jewish music societies (Jakubczyk-Ślęczka 2020), as well as by well-known music composers and performers who were numerous on the Polish popular music scene of that period (Gliński 2014; Zimek, Jankowski 2019). In this context, Kozłowski appears to be simply a child of his epoch and – only and as much as – one of the last close witnesses of traditional Jewish music life.

The klezmer of his times

Leopold’s father used to instruct the members of his band by saying: ‘A klezmer has to be able to play everything. Not for money, but for his own ambition. And for the people who need it’ (Cygan, p. 86). So when Leopold decided to be a musician, he explained this decision by saying that he did it ‘for these new people, who also needed music’ (Cygan, p. 86). According to his own words, he also ‘tried to continue the form and content’ of traditional Jewish music (Cygan, p. 152). Therefore, even without memorizing too many old klezmer melodies, he maintained the social function of a klezmer.

‘The new people’ he mentioned in his biography were initially the Russians who captured Przemyślany on September 19 , 1939, the 19th day of the Second World War and just two days after the USSR’s attack on Poland from the east. Playing for them extended his repertoire to include Soviet music. In 1941, the city was taken over by the Germans. Leopold’s father, his younger brother and he himself decided to run away from Przemyślany. Heading east and seeing no hope for improvement of their situation, they decided to return to Leopold’s mother. Unfortunately, in November 1941, the Nazis ordered all Jewish males over 16 to gather in the city center. This was the last time he saw his father.

In 1943, Kozłowski was forced to play the accordion in the Nazi labour camp in Jaktorów. This saved his family’s life when the Nazis decided to liquidate the ghetto of Przemyślany, as Leopold could request to transfer them to the camp. There, he again played popular music for partying Germans as well as German military marches for prisoners leaving and returning from work outside the camp. He did the same in the next labor camp in Kurowice until the Nazis decided to close it down in July 1943. At that time, Leopold saved his mother, brother, and himself with the help of Polish partisans. He and Dolko joined them in the nearby forests. They hid their mother in the barn of a Ukrainian peasant, but the next day they found her dead. She had been killed by Nazi soldiers sweeping the area. In 1944, Dolko was also killed by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which was carrying out ethnic cleansing in Eastern Galicia.

Having lost his loved ones, Leopold was left just with his friends from the 1st Company of the 44th Regiment of Infantry. Even after the war, he decided to remain a soldier. Around the turn of 1945 and 1946, he settled in Kraków where, in 1947, he set up a military band. He started with a 12-person orchestra and a choir, but he developed these ensembles into a full symphonic orchestra, a 50-person choir, and 8 pairs of ballet dancers who won the Polish Overview of Military Bands in 1953. In 1956, he got a diploma of the Music Academy in Krakow, formally becoming a professional conductor. As an arranger and composer of military music as well as a conductor of military bands, he achieved many successes. Eventually, in 1967, he became the director of the Military Song Festival in Kołobrzeg. But not for long. March 1968 brought the peak of a political crisis in Poland which eventually led to an antisemitic campaign. The political and social harassment of Polish Jews forced most of them to emigrate. For Leopold, it meant the end of his military career and life in military service.

Despite this adversity, he decided to remain in Poland. In 1969, his friends offered him a job of a consultant for the Song and Dance Ensemble ‘Rzeszowiacy’ in Mielec. Once again, he did more than he was asked for. He set up a big band in Mielec and then in Krosno. In the 1970s, he started collaborating with the Jewish Theater in Warsaw, for which he prepared an

What about klezmer repertoire?

Leopold never stopped being a klezmer and he always followed his father’s ideals. Being a typical klezmer, his music accompanied ordinary people in their everyday life events, telling the history of the Jews. In the 1970s, as previously mentioned, he started cooperating with the Jewish Theater in Warsaw. Also, his adaptation of ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ had been staged since the 1980s in Music Theater in Gdynia, Wrocław Operetta, Krakow Operetta, Great Theater in Warsaw, Entertainment Theater in Chorzów ,as well as in Wrocław in Hala Stulecia (a production made in cooperation with Wrocław Opera House).

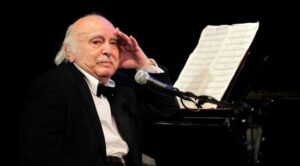

A spontaneous performance at the Hotel ‘Alef’ located in Krakow’s Kazimierz (a prewar Jewish district), turned out to be a turning point in his life after 1989. In 1994, he accompanied Jacek Cygan on the piano for some Jewish songs translated by the latter into Polish. This became the starting point of their future collaboration. Joined by some Polish singers, musicians, and actors, they started staging public performances. Every year, they gave a concert during the Jewish Culture Festival in Krakow. They also recorded two CDs with old and new Yiddish songs arranged or composed by Leopold Kozłowski and translated or written in Polish by his friend, Jacek Cygan (2002).

In their repertoire, there is, among others, the original Kozłowski’s song ‘Gdy jedna łza’ (’When one tear drops…’) in which he used the rhythm of traditional klezmer hora/zhok. He brought back songs from the Jewish tradition written by prewar Jewish folk musicians from Poland, like Mordekhai Gebirtig or Nakhum Sternheim, and reinstated them in Polish concert life. There were also many humoristic songs in his repertoire, presenting Jewish life in an easy, approachable way. One of them is the song ‘Bo on jest klezmer’ (‘For he is a klezmer’), which is a confession of a girl who fell in love with a Jewish musician. Unfortunately, he happened to be more interested in playing the clarinet than in her, for which she mocks him by using funny onomatopoeic tricks in her song.

In Kozłowski’s repertoire, there are also original and important songs, some of them even symbolic. For example, ‘Ballada o Szmuliku’ (‘Ballade about Shmulik’) tells the story of a prewar Jewish shoemaker from Krakow’s Kazimierz who, during Nazi occupation, posed as a blind beggar sitting in front of St. Cathrine’s church and playing Chassidic melodies on the accordion. The song concludes with the words: ‘Apparently the Lord wanted, seeing so much harm, the Jewish life to be saved at least once by the cross’. Listening to it, former Kraków cardinal Franciszek Macharski, is believed to have called it the most ecumenical song he had ever heard (Cygan, 197).

One of the most touching songs by Kozłowski is ‘Tak jak malował pan Chagall’ (‘Just as Mr. Chagall painted it’). Its lyrics were written by Polish poet and singer, Wojciech Młynarski, who was inspired by the performance he had watched at the Jewish Theater in Warsaw, ‘Bonjour Monsieur Chagall’ (premiere in 1979, with music arranged by Kozłowski). Impressed by this performance, Młynarski asked Kozłowski to compose the music for his lyrics. Kozłowski later recalled that he treated this task as his tribute to the Jewish people expelled from Poland during the antisemitic campaign in 1968.

The chronicler, the visionary, the bellwether

Leopold Kozłowski’s works have never been a subject of academic analyses, neither musicological nor sociological. The historical, social and aesthetic values of his compositions have never been given thought. Kozłowski himself – as the music icon of postwar Kazimierz – has never been regarded as a social and cultural idol, and therefore has not been a subject of critical reflection.

It seems that now is the time to ‘blow out the dust of non-remembrance’ and ask what he wanted to tell us as a chronicler of the recent history of Polish Jews? What may he teach us as a bitterly experienced human and a sensitive artist who probably can “see more”? What could we see if we let him be a bellwether leading us through the newest history of the Polish-Jewish relations?

Bibliography

- Cygan Jacek, Klezmer: Opowieść o życiu Leopolda Kozłowskiego-Kleinmana, Kraków-Budapeszt 2009.

- Feldman Walter Zev, Remembrance of Things Past: Klezmer Musicians of Galicia, 1870-1940, [in:] ‘Polin. Studies in Polish Jewry: Focusing on Jewish Popular Culture and Its Afterlife’, ed. M. C. Steinlauf, A. Polonsky, 2003 vol. 16, p. 29-58.

- Gliński Mikołaj, Polska piosenka pochodzenia żydowskiego, 2014.

- Jakubczyk-Ślęczka Sylwia, Jewish Music Organizations in Interwar Galicia, [in:] ‘Polin. Studies in Polish Jewry: Jews and Music-Making in the Polish Lands’, ed. F. Guesnet, B. Matis, A. Polonsky, 2020 vol. 32, p. 343-370.

- Jankowski Tomasz, Zimek Katarzyna, Hebrew Tango in Interwar Poland, Warsaw 2019.

- Ostatni klezmer. Leopold Kozłowski i przyjaciele [CD], WFDiF 2017.

Reports from the ceremony at the Jagiellonian University.

- Do Instytutu Muzykologii UJ trafiła Kolekcja Leopolda Kozłowskiego, the official website of the Jagiellonian University

- Muzyczna kolekcja ostatniego klezmera Galicji przekazana Instytutowi Muzykologii UJ, the official website of Kraków TV Channel

- Niezwykły dar Marty Kozłowskiej-Woźniak, córki ostatniego „klezmera Galicji”, the official website of Radio Kraków

- Uroczystość przekazania Instytutowi Muzykologii UJ „Kolekcji Leopolda Kozłowskiego” – relacje, the official website of the Musicology Institute at the Jagiellonian University

——————————-

Sylwia Jakubczyk-Ślęczka is a musicologist, faculty member at the Musicology Institute of Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland. Her primary research interest lies in the musical life of Galician Jews. She is the author of numerous articles on the topic, as well as a monograph on prewar Krakow cantor, Eliezer Goldberg: galicyjski mistrz żydowskiej kompozycji i harmonii (Eliezer Goldberg: Galician Master of the Jewish Composition and Harmony).