By Hervé Roten

On May 21, 1856, the conference of the French chief rabbis, presided by the chief rabbi of France Salomon Ulmann (1806 – 1865), endorsed the use of the organ in the Consistorial temples. This decision was subject of a lively debate between the holders of Orthodox Judaism and the reformers. And the text which was finally adopted was clearly the result of a compromise: “The Conference, while regretting the tendency to join to the religious services a pump, barely compatible with the nature of simplicity which marks the Israelite cult, declares in a doctrinal point of view: it is allowed to introduce the organ in the temples, and to be touched, on Shabath and holidays, by a non-Israelite. However, the establishment of an organ in the synagogues can only take place with the approval of the chief rabbi of the District, on the requirement of the communal rabbi”[1]http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/sklein.htm, Salomon (Schlôme) Wolf KLEIN, Chief Rabbin of Colmar and of the High-Rhine (1814 – 1867) by Paul KLEIN (Moché Catane), Excerpt from the … Lire la suite

The publication of the rabbinic decision is nevertheless a triumph for the holders of the reform of the French consistorial cult. But it only makes recognize a practice already present in various Israelite temples since several years.

We can therefore legitimately ask ourselves the following question: why did the introduction of the organ in the public cult raise such a polemic among the rabbis and the worshippers?

I. Music and Judaism

To answer this question, one must recall the age-old suspicion of the rabbinic authorities toward music. According to Maimonides (1135-1204), music is tolerated only for prayer[2]Maimonides (1135-1204), whose rigorous attitude towards music was often observed, adjusted in his famous responsum his opposition to music in the following words : “Prohibition of any musical … Lire la suite. In ancient times, music – in particular instrumental – was often associated to the pagan cults. The biblical narratives which describe the cult during the time of the two Temples attributed to it, however, a large part. Thus the service of the Temple required no less than 288 musicians playing various instruments, mainly string and wind instruments.

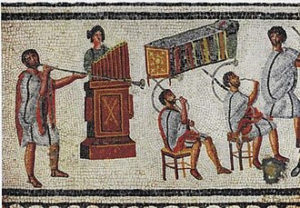

The Talmudic literature relates even the magrefah (Tamid, Chap. V, Mishnah VI) to the ancestor of the organ. This instrument, sometimes described as a kind of pan-pipe or a Roman hydraulis (pipe organ), would have been constituted of a box containing 10 empty reeds, each one presenting 10 holes, corresponding to 10 different notes (thus a hundred notes). This instrument would have been used to call the priests and the Levites to their duties, its sonority being so powerful that one could hear it up to Jericho (!). This story, more symbolic than scientific, is today questioned by many musicologists to whom the magrefah was just a tool (a rake or a shovel?) thrown on the ground after having cleaned the altar of the Temple, in order to call the singers to continue their service.[3]Batja Bayer, Encyclopaedia Judaïca, vol. 12, p. 566. See also the article « The Musical Magrepha of the Temple » on the website … Lire la suite

The destruction of the second Temple in 70 after J.-C., and the development of the synagogue marked the prohibition of any instrumental practice in the cult. Only the use of the shofar[4]Goat or ram horn in which one blows. was still authorized in the synagogue, and still, mainly during the celebrations of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It is true that before being considered as a musical instrument, the shofar was a symbolic reference to Isaac’s sacrifice, and the alliance between God and the children of Abraham.

However, in facts, the musical practices were more flexible: they depended on the approach, more or less caring, of the local rabbinic authorities. Thus the music was often encouraged for certain services, such as the Jewish carnival of Purim, weddings and circumcisions. In the 12th century, Petayah of Regensburg who was visiting Bagdad, even noted that some Psalms were sung on days of semi-celebration with a musical accompaniment (Itinéraires, ed. Principes, 2ro). In the 13th century, the Provencal Menahem Me’irî related that the Spanish Jews established in Perpignan used to practice profane instrumental music, even on the day of Shabbat (Magen abôt, ed. I. Last, ch. 10). And this community was however very orthodox as its members claimed themselves from the great Talmudist, exegete and Kabbalistic theologist Nahmanide (1195-1270)!

In Northern Italy, the reinforcement of the segregation due to the Counter-Reform of the middle of the 16th century incited many professional Jewish musicians to practice their work inside of ghettos and synagogues. Despite the objection of several rabbinic authorities, this movement got amplified in the first half of the 17th century under the impulse of the rabbi and musician Léon de Modène (1571-1648). In 1605, this rabbi – who claimed that he had had no less than 26 different professions during his career! – introduced to the synagogue of the community of Ferrare a choral practice for the occasion of certain Shabbat and holiday celebrations. Between 1628 and 1639, he ran in Venice the activities of a Jewish musical association, first called Accademia degli impedeti and then Compagnia dei Musici. According to several testimonies, this association was able to mobilize two choirs and instrumentalists – among which one organ – to prepare the celebration of Simchat Torah.[5]Cf. Hervé Roten, Musiques liturgiques juives : parcours et escales, Coll. Musiques du monde, Cité de la Musique / Actes Sud, 1998, p. 60

Still in the 17th century, but in Prague this time, the singers of the prayer Barukh she-Amar (Mezammerei Barukh she-Amar) performed instrumental music in the synagogue every Friday afternoon. Abraham Levi of Amsterdam, who was passing through Prague between 1719 et 1724, noticed that “the cantors also used organs, cymbals, harpsichords and string [instruments] every Friday for the welcoming of the Sabbath ; they sang not only Lekhah dodi with these instruments, but they continued to play and sing a “pot-pourri” of fine melodies for more than an hour”. Such practices also took place regularly in the synagogues of Frankfort, Nikolsburg and many other towns.[6]Hervé Roten, ibidem, p. 57.

These reform ideas led to the notation of the first collections of synagogue music around the middle of the 17th century. In 1744, Juda Elias of Hanover wrote the first manuscript of music noted by an Ashkenazi cantor. He was then followed by Aaron Beer (1738-1821) whose 1765’s manuscript contains no less than 447 melodies for the prayers of Jewish holidays! Most of them are compositions by Aaron Beer himself or of his contemporaries, which are often pale imitations of the 18th century’s instrumental style, in which we find very few traces from traditional Ashkenazic modes.[7]Hervé Roten, ibidem, p. 68.

This assimilation of a part of Jewish music to Western Art music also took place in the Sephardi community of Amsterdam during the 18th century. But it narrowed itself only to some specific pieces: choral works and cantatas intended for particular Shabbat services (Shabbat nahamou, Shabbat bereshit, etc.) and holidays such as Sukkot or Simchat Torah.

II. The reform of the cult in the 19th century

The idea of Judaism embedded to the society of its time started in Germany with Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786), leader of the Haskalah (movement of the Jewish Enlightenment), who initiated the first steps of what would become reformed Judaism.

Translator of the Bible in German, he encouraged his followers to modernize the religious education and to study profane fields. Faith and reason, his key-words, opened the gate to Science of Judaism (Wissenschaft des Judentums) which emerged in Germany in the beginning of the 19th century, and from which Leopold Zunz (1794–1886) was one of the leading figures.

At the same time, secular leaders such as Israël Jacobson (1768–1828) expressed their will to modernize the cult in the synagogue: alleviated liturgy, introduction of the organ, recitation of prayers in German and sermons bearing moral teachings. Thus in 1801, Israël Jacobson established in Seesen, in Saxe, a school in which 40 Jewish children and 40 Christian children studied together. Then from 1810, the Jewish community of Seesen was the first one to introduce the regular usage of the organ in its religious services. It was followed by the communities of Kassel, Berlin (1815) and Hamburg (1818).

- Musical ex. 1: Vor Dir, o Gott (In front of you, oh God) – Communitarian hymn (excerpt)[8]The musical examples 1 and 2 are excerpts from the CD Die Musiktradition der Jüdischen Reform-Gemeinde zu Berlin (The musical tradition of the Jewish Reform Congregation in Berlin), Tel Aviv, … Lire la suite

This prayer from the reformed synagogue of Berlin was sang in German on the melody of a choral by Georg Neumark (1621 – 1681) during Roch Hachanah’s morning service. The prelude of the organ is taken from the prayer Untane tokef by Louis Lewandowski.

- Musical ex. 2: Sh’ma Yisrael (excerpt)

Traditional music for Yom Kippur recorded in the reformed synagogue of Berlin on December 14, 1929. Arrangement : J. Stern. Soloist : Joseph Schmidt (tenor).

The musical conclusion on the organ is taken from the prayer Seou shearim by Louis Lewandowski.

This reformed cult provoked a lively polemic with the most Orthodox people of the Jewish community, who, with the support of the rabbinic authorities of Germany, Poland, France, Italy, Bohemia-Moravia and Hungary, published in 1819 in Hamburg a book called Ele diverei ha-Berith (Here are the words of the Alliance) calling to resist to the “new religion”.

The frontispiece of the book announced clearly its goal:

It is forbidden:

– To change anything to the text of the prayers in usage in Israel, from the morning prayers up to the ‘Alenu, and even more to make deletions.

– To pray in another language than Hebrew, any prayer book which was printed differently than according to the tradition and to our practices being therefore unfit to be used and cannot be used for prayer.

– To use in the synagogues musical instruments, such as an organ, on Shabbat and holidays, even if it is played by a non-Jew.[9]Cf. Jacques Kohn, Orgue et bima (http://judaisme.sdv.fr/perso/jackohn/orgue.htm).

Despite this opposition, this “ordered service” (geordneter Gottesdienst) spread out all along the 19th century in many communities of Western Europe and other Jewish centers, in Particular in USA. Its dissemination was facilitated in a large part by the acts of a few cantors and talented musicians such as Israël Lovy (1773-1832) in Paris, or Maier Kohn (1802-1875) in Munich. Israël Lovy was the first Chazan (cantor) to introduce the choral singing with four voices in the new consistorial synagogue of Notre Dame de Nazareth (Paris)[10]Lovy’s music combines the ancient style of the meshorerim (vocal duet bass- soprano a little boy accompanying the Chazan) with the choral style of the comic opera. Maier Kohn, furnished and … Lire la suite. Among the main cantors of the new synagogue service, let’s mention also the names of Salomon Sulzer in Vienna (from 1826), Hirsch Weintraub in Koenigsberg (1838), Louis Lewandowski in Berlin (1840) or Samuel Naumbourg in Paris (1845). These verious Chazanim composed melodies for the prayers in a pure tonal style without rejecting the ancient synagogue chants which they try to harmonize. For this, they collected many traditional melodies in order to add a choral or instrumental arrangement.

The new synagogue service azlso influenced East European’s Chazanut. Cantors, such as Osias Abrass, Jacob Bachmann, Nissan Blumental, Wolf Shestapol, Spitzburg and many others, came to study in Vienna with Sulzer, or were inspired by his musical conception. But it was only in 1901 that appeared the first organ – symbol of reformed Judaism – in the temple of Odessa (Russia).

- Musical ex. 3: Kadish of Musaf – Salomon Sulzer (1804-1890) (excerpt)[11]CD Das Lied der Lieder – Festtags gesange des Wiener Statdtempels, ORF Studio Vienne 3/W09-610, 1993

This piece is performed by Shmuel Barzilai and the Tempelchor des Wiener Stadttempels under the dirction of Lev Vernik ; on the organ : Raymond Goldstein.

III. The controversy surrounding the introduction of the organ in the synagogues of France

In France, the introduction of the organ in the public cult was also very progressive. The instrument was first used for official ceremonies. In this way, in 1806, the Parisian temple of the rue Saint-Avoye celebrated Napoléon Ist’s birthday. Accompanied by a choir, the rabbi Abraham Andrade sang a hymn in honor of the Emperor, and the orchestra performed a symphony by Haydn[12]Hervé Roten, Les traditions musicales judéo-portugaises en France, Paris, Maisonneuve & Larose, 2000, p. 37.. On August 15, 1809, the Emperor’s birthday was once more celebrated in the temple. A Sephardi chazan, called Dacosta, was put in charge of the musical organization, which planned a singer, who is not a chazan, Abraham Brandoni, altar boys, accompanied by two harps and an organized piano (maybe an ancestor of the harmonium?)[13]Gérard Ganvert, La musique synagogale à Paris à l’époque du premier temple consistorial (1822-1874), doctorate PhD of the third cycle, University Paris IV Sorbonne – U.E.R. of … Lire la suite.

In Bordeaux, several testimonies showed that the harmonium was used way before its definitive establishment in the new synagogue inaugurated in 1882. Thus, the party in honor of the king Louis-Philippe was celebrated on May 1, 1833 by a Te Deum with an accompaniment on the « organ ». The ceremony of the re-opening of the temple of the rue Causserouge (closed for repairs), in 1843, featured an « organ » played by a man called M. Dellile, who was, according to the Consistory: « one of the most skilled organ player of the town ». In a letter dated December 11, 1855, it was asked that the wedding of the Chief Rabbi Marx’s daughter should be celebrated « with all pomp and circumstance », which would thus allow a « piano-organ » (that is a harmonium) accompanying “the chorals which must be sang on this occasion“[14]Julien Grassen-Barbe, La musique synagogale bordelaise au XIXe siècle, op.cit., p. 54-59..

In Paris, the Ashkenazi synagogue of the rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth used the piano or the organ during various services, such as the religious initiation, a ritual that was introduced in 1842, following the example of the Christian solemn communion. The wedding of the chief rabbi Marchand Ennery’s daughter was celebrated in 1846 where featured an organ.[15]Cf. Dominique Jarassé, La synagogue de la rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth, lieu de construction d’une culture juive parisienne et d’un regard sur les Juifs … Lire la suite

In the capital city, the debate about the introduction of the organ in the synagogues was strong and violent since 1844, the year when the secular members of the Paris Consistory asked the chief rabbi Isidor the authorization to use an expressive organ for a ceremony of initiation in which young girls would sing a hymn. The latter refused, arguing that “although there is no formal text against the introduction of this instrument in the temple, he believes he must firmly oppose himself to it, since this usage is similar to those of the non-Israelite cults…”[16]Record of the minutes of the sessions of the Consistory of Paris, (cote AA3 des Archives Consistoriales, séance du ? mars 1844, pp. 216-217. Mentioned by Gérard Ganvert, La musique synagogale à … Lire la suite

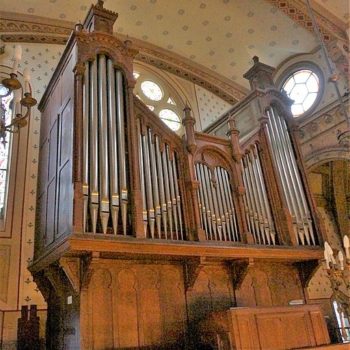

The Central Consistory, requested to settle this disagreement, deferred the ceremony for several months and promised to take a decision on this matter. But the debate was launched, and from 1851, the Paris Consistory decided to set an organ in the temple of the rue Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth that was then being rebuilt. At the same time the Portuguese Jews of the capital city built a new temple on number 23 of the rue Lamartine, in which they planned to set also an organ, placed behind the choir.

And it’s with the sound of this instrument[17]According to Maurice Bourge, (Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris, n° 46, 1854, p. 367-368), it is « a pretty organ of eight registers and two keyboards, built Ducroquet house with dimensions … Lire la suite that was inaugurated on June 4, 1851, the first consistorial synagogue possessing an organ.

« The ceremony started with the transport of the Sepharim into the Hechal (…). During this procession, we heard a solo of organ. (…) We noticed that in the procession of the Sepharim, the Ashkenazi cantors of the Temple joined the choir. (…) We then took out five Sepharim; this was accompanied by a solo of organ. »[18]Les Archives Israélites, tome XII, 1851, p. 310-311.

On this matter, we can notice that the Sephardi Portuguese Jews were generally more open to the reform than the Ashkenazi rabbis. This probably came from the fact that the Portuguese Jews were much more integrated than their co-religionists from Alsace-Lorraine.

In his report published in October 1855 in “l’Univers israélite”, S. Bloch wrote:

« In the Portuguese Temple, things went normally, that is with dignity and a great pump. The organ played again during the celebration of Rosh Hashana, but it fasted on the day of Kippur, as even its most passionate supporters wouldn’t have wanted to add anything to the beautiful prayer Col Nidré (…).. »[19]S. Bloch, L’Univers israélite, n° 2 – October 1855, pp. 54-56

In December 1855, he precised : « The organ is played on Friday nights, Saturdays and for High Holidays in the Portuguese Temple, but not in Notre-Dame de Nazareth. »[20]S. Bloch, L’Univers israélite, n° 4 – December 1855, pp. 263-264

A proof of this integration of the organ in the Portuguese public cult, Emile Jonas, the music director of the temple of the rue Lamartine, published in 1854 a book called Shirot Yiserael, Recueil des chants hébraïques anciens et modernes, exécutés au Temple de rit portugais de Paris (Compilation of ancient and modern Hebraic chants, performed in the Portuguese Temple of Paris), comprising 39 liturgical chants with an organ accompaniment.

- Musical ex. 4: Tehilat – Emile Jonas (1827-1905)[21]Excerpt from the CD Jacques Offenbach and friends – from the synagogue to the opera, Ed of the EIJM, 2019.

The temples on the rue Lamartine (1851) Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth (1852), la Victoire (1874) and Buffault (1877) were thus the four first parisian synagogues equipped with an organ[22]The synagogue of la Victoire possesses a Merklin Organ (1875) featuring two keyboards of 56 notes each and a pedalboard of 30 notes, rehabilitated in 1960 by the Gutschenritter House. The synagogue … Lire la suite.

in 1882, Bordeaux also set an organ in his new temple.

In the Alsace-Lorraine region, a major place of Jewish settlement, the situation was more contrasting. According to Claude Heymann, « The Alsatian Chazanim of the middle of the 19th century possessed musical notions, but scarcely went to the music conservatory. (…) If the Alsatian Jews are, as a whole, very attached to the melody of the prayers or the nigunim that they hear in the synagogue and that the peddlers hum all year long during their travels, they prefer without any doubt the spontaneous fervor of a shaliah tsibbur (amateur cantor) guiding the community singing to a tenor that would transform the synagogue into an opera. Nothing is more characteristic than the outrage of one of the characters of the writor Léon Cahun (1841-1900) who said: « It seems that in Frankfort and Paris we built synagogues with organs, and that we make sing altar boys. Organs! Organs! Why not a church and the mess right away! See the idolatry of this new age! »[23]Heymann Claude, Vie communautaire, spiritualité et musique dans la campagne alsacienne. Le rôle des chantres, Archives juives 2002/1 – N° 35, p. 131.

Among the fierce opponents to the organ, let’s mention the chief rabbi Salomon Klein of Colmar (1814-1867) who firmly opposed himself, during the 1856 conference of French chief rabbis, to the introduction of the organ in the public cult[24]Cf. http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/sklein.htm .

We can summarize his arguments with the following:

– To play music during Sabbath, or make it play by a non-Jew, is a forbidden “work” (shevuth).

This prohibition is expressed in the clearest way by Rambam/Maimonides (Hilkhoth Shabbath 23, 4) and by the Shul‘han ‘arukh (Ora‘h ‘hayyim 338 and 339).

– Let us remind that since the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, it is forbidden to use musical instruments, with the sole exception of wedding celebrations (Shul‘han ‘arukh Ora‘h ‘hayyim 560, 3).

– The use of the organ in the synagogues faces another prohibition, the one of imitating the habits followed by the non-Jews (ולא תלכו בחקת הגוי אשר אני משלח מפניכם [Wayiqra 20, 23]).[25]Cf. Jacques Kohn, Orgue et bima, op. cit.

The position of Salomon Klein was strongly fought by Gerson-Levy, in his book Orgue et pioutim (Organ and piyutim), published in Metz in 1859. The subtitle of this book is insightful: « Appeal to common sense about these two questions: is the organ anti-religious? Does the rhymed prose of the Middle-Age have a characteristic of stability in the French synagogue? »

According to Gerson-Levy, the ancient synagogue was « a place where each one was master: no taste, no order, no respect, no discipline. The main officer usually had a nasal voice whose trills imitated the snorts of a horse, with a basso-profundo vocal accompaniment whose only merit was to counterfeit the growl of an animal hated y the Israelites [a pig], and a discording falsetto resembling to the sour and screeching voice of a young girl; the whole assembly made a chorus with this trio, and not one knew the scale. » The same Gerson-Levy had nevertheless the honesty to admit after all: « Our fathers found it pretty, especially when there was a lot of fanfare, a lot of waltzes and a lot of ariettas ». (p. 4) But he then insisted on the need to reform the cult. « Listen ! Reform, according to all the dictionaries, is the re-establishment of the ancient form, the retrenchment of all the abuses that deformed it » (p. 6).

Then he denied one by one the arguments of the opponents to the organ:

« According to M. Marchand Ennery’ s dictionary, the Ugab invented by Yuval would have only been an organ » (sic). (…) Kings David and Salomon did not fear to introduce 4.000 instrumentalists for the house of God. (…) We agree completely about the absence of the organ in the Temple of Salomon; it wasn’t there, just like the saxhorn, the ophicleide, the violin, the lightning rod, the gas lighting and the electrical telegraph weren’t there. Is it its fault if it wasn’t born yet? The organ was not born with Christianism. 135 years before the birth of Jesus, its concept was developed by a mathematician from Alexandria, named Ctesibius. » (p. 8)

Another objection from that time: « Which religious feeling can produce on an Israelite heart an instrument touched by a non-Israelite? ». (p. 14)

To this objection, Gerson-Levy answered that « the Temple of Salomon, like many other synagogues, were built by non-Jews. As well as the printing of religious books by non-Jews» (p. 16)

As for the prohibition of the use of the organ on the Sabbath, for Gerson-Levy, it was just a safety precaution. « The instrument could break down and one would have to fix it, which implies a forbidden work on the Sabbath. But this case is unlikely, as the organ player is not an instrument maker, and even if he wanted to repair it, the assembly of worshippers would remind him to the observance of the Law. » (pp. 16-17).

To finish, Gerson-Levy concluded:

« I do not pretend that the organ is essential in the synagogue or in the church, but I insist on thinking that the rabbi who wishes to prohibit it, under the justification of Huqat goyim (custom of the goyim, editor’s note), lies to science and to his conscience… » (p. 17).

In the last third of the 19th century, except in Colmar, the organ succeeded to be established in almost all the big communities of Alsace region, even on shabbat and holidays. In small communities, with the exception of Brumath, Benfeld and Selestat, the organ was not played on shabbat or holidays.[26]Cf. Heymann Claude, Vie communautaire, spiritualité et musique dans la campagne alsacienne. Le rôle des chantres, Archives juives 2002/1 – N° 35, p. 133.

The use of the organ continued in the 20th century. In Metz, the Chazanim Jules Ptachek Salomon Binn (Chazan from 1919 to 1953) and Albert Kirch (from 1950 to 1982) officiated for several decades, with an organ. Salomon Binn also led the direction of the choir of the synagogue of Metz. Max Rosenzweig (1902 – 1977) followed him between 1934 and 1967 as conductor and organist. His son recalled that at that time, « the Israelite Consistory of Metz was sophisticated and not too observant of the orthodox principles. Thus, the choir, which should have been composed only of men like in Strasbourg, was here, mixt, and accompanied, except on Yom Kippur, by an organ. The restriction imposed: the organist could not be Jewish… The German songs were almost all classical and musically pretty. » (…) « The choir was accompanied in the Synagogue by Monsieur Marcel Mercier on the organ, a piano teacher in the music academy of Metz: he even played during the Shabatoth and holidays, because Monsieur Mercier was a Christian. Another Christian organist, whose name I forgot, substituted Monsieur Mercier, when the latter could not do it. Sometimes, it was the dentist Sylvain Binn, son of the Chazan Salomon Binn, who accompanied voluntarily the choir on the organ, on weekdays. »[27]Jean Jonathan Rosen, Max (Moché) ROSENZWEIG 1902 – 1977, Director of the synagogue choir of Metz between 1934 and 1967, http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/hazanim/rosenzw.htm

- Musical ex. 5: Enoch kehotsir de Louis Lewandowski par la chorale de Metz[28]CD recorded by Albert Kirch, track 12.

Today, the organ of Metz, like many of its « colleagues » is no longer used. The Jewish typography profoundly changed during the 20th century, especially with the deportation of one third of the Jews from France and the massive arrival of North African Jews in the 1950-1960’s.

In May 1968, the protest movements that happened inside the French society reached the synagogue… but in the sense of a return to a bigger orthodoxy. On a Friday, around mid-May, students from the Bne Akiba, a religious Zionist group led by the rabbi Paul Roitman, arrived to the Parisian great synagogue of the rue de la Victoire and threatened to break down the organ if it was used. On that same evening, the chorists, stopped by a subway strike, did not arrive to the synagogue. The rabbinic authorities, with at their head the chief rabbi of Paris Meyer Jaïs, took this opportunity to request the abandonment of the organ and of mixed choirs. The rabbinate was divided; finally the organ took its place back in the cult but for accompanying male choirs only. Mixed choirs were sung only for weddings, before being definitely forbidden by the Chief Rabbi Kaplan in November 1975.

It’s also at that time, in 1973, that had been closed the one and only school of cantorial art established at the Israelite Seminary of the rue Vauquelin in Paris. The apprentice cantors could acquire there a general musical knowledge (solfeggio, vocal techniques, piano) as well as the learning of prayers in the two main rites, Ashkenazi and Sephardi (Portuguese)

Since the end of the 1970’s, a certain form of orthodoxy took place, and except for the reformed synagogues, weddings or official ceremonies, the organ is not played anymore in French synagogues.

Conclusion

For more than 150 years, the organ was the emblematic instrument of the emancipation of the Jews. Its usage, more present in the big agglomerations than in small provincial towns or in the countryside, was adapted to the spacialization of the new consistorial temples, of which its greatness and solemnity were to mark the regeneration of the French citizen of Jewish religion. Until 1874, the consistorial authorities even tried to merge the two main rites, Portuguese Sephardi and Ashkenazi, into one unique French rite, but this attempt failed.

This unitary conception, considered sometimes as an elitist one, was useful in its time as it allowed the integration of the Jews inside the French society. But today, facing the spreading of places of cult and the return to a more Orthodox Judaism, most of the worshippers (except those affiliated to the reformed movements) find their way back to the synagogues or small oratories where a cappella voices are heard again.

Three examples of prayers accompanied by the organ, written by Jewish composers of the 19th century

(Excerpts from the CD Jacques Offenbach and friends – from the synagogue to the opera, Ed of the EIJM, 2019.)

Musical ex. 6: Mizmor lessodo (Ps. 100), Fromental Halévy (1799-1862)

Musical ex. 7: Kedouschah de Moussaph, Jules Erlanger (1830-1895)

Musical ex. 8: Ouvnou’ho yomar, Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864), arrangement : Samuel Naumbourg

| 1 | http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/sklein.htm, Salomon (Schlôme) Wolf KLEIN, Chief Rabbin of Colmar and of the High-Rhine (1814 – 1867) by Paul KLEIN (Moché Catane), Excerpt from the Bulletin de nos Communautés, 1955. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Maimonides (1135-1204), whose rigorous attitude towards music was often observed, adjusted in his famous responsum his opposition to music in the following words : “Prohibition of any musical practice, be it vocal or instrumental, except for the prayer (where music) helps and awakens the soul to joy and sadness” (ed. A.H. Freimann, n° 370) |

| 3 | Batja Bayer, Encyclopaedia Judaïca, vol. 12, p. 566. See also the article « The Musical Magrepha of the Temple » on the website https://www.beishamikdashtopics.com/2014/10/the-musical-magrepha-of-temple.html |

| 4 | Goat or ram horn in which one blows. |

| 5 | Cf. Hervé Roten, Musiques liturgiques juives : parcours et escales, Coll. Musiques du monde, Cité de la Musique / Actes Sud, 1998, p. 60 |

| 6 | Hervé Roten, ibidem, p. 57. |

| 7 | Hervé Roten, ibidem, p. 68. |

| 8 | The musical examples 1 and 2 are excerpts from the CD Die Musiktradition der Jüdischen Reform-Gemeinde zu Berlin (The musical tradition of the Jewish Reform Congregation in Berlin), Tel Aviv, Israel, Beth Hatefutoth, ℗1997 |

| 9 | Cf. Jacques Kohn, Orgue et bima (http://judaisme.sdv.fr/perso/jackohn/orgue.htm). |

| 10 |

Lovy’s music combines the ancient style of the meshorerim (vocal duet bass- soprano a little boy accompanying the Chazan) with the choral style of the comic opera. Maier Kohn, furnished and compiled in his book Münchner Terzettgesänge (1839) many compositions or harmonized arrangements of synagogue melodies |

| 11 | CD Das Lied der Lieder – Festtags gesange des Wiener Statdtempels, ORF Studio Vienne 3/W09-610, 1993 |

| 12 | Hervé Roten, Les traditions musicales judéo-portugaises en France, Paris, Maisonneuve & Larose, 2000, p. 37. |

| 13 | Gérard Ganvert, La musique synagogale à Paris à l’époque du premier temple consistorial (1822-1874), doctorate PhD of the third cycle, University Paris IV Sorbonne – U.E.R. of Musicology, 1984, p. 62. |

| 14 | Julien Grassen-Barbe, La musique synagogale bordelaise au XIXe siècle, op.cit., p. 54-59. |

| 15 | Cf. Dominique Jarassé, La synagogue de la rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth, lieu de construction d’une culture juive parisienne et d’un regard sur les Juifs (https://www.cairn.info/revue-romantisme-2004-3-page-43.htm). |

| 16 | Record of the minutes of the sessions of the Consistory of Paris, (cote AA3 des Archives Consistoriales, séance du ? mars 1844, pp. 216-217. Mentioned by Gérard Ganvert, La musique synagogale à Paris à l’époque du premier temple consistorial (1822-1874), op.cit., p. 76. |

| 17 | According to Maurice Bourge, (Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris, n° 46, 1854, p. 367-368), it is « a pretty organ of eight registers and two keyboards, built Ducroquet house with dimensions compatible to the size of the sanctuary, more elegant than vast. » |

| 18 | Les Archives Israélites, tome XII, 1851, p. 310-311. |

| 19 | S. Bloch, L’Univers israélite, n° 2 – October 1855, pp. 54-56 |

| 20 | S. Bloch, L’Univers israélite, n° 4 – December 1855, pp. 263-264 |

| 21 | Excerpt from the CD Jacques Offenbach and friends – from the synagogue to the opera, Ed of the EIJM, 2019. |

| 22 | The synagogue of la Victoire possesses a Merklin Organ (1875) featuring two keyboards of 56 notes each and a pedalboard of 30 notes, rehabilitated in 1960 by the Gutschenritter House. The synagogue of the rue Buffault has an organ of the same size, rebuilt by the same organ maker in 1985. |

| 23 | Heymann Claude, Vie communautaire, spiritualité et musique dans la campagne alsacienne. Le rôle des chantres, Archives juives 2002/1 – N° 35, p. 131. |

| 24 | Cf. http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/sklein.htm |

| 25 | Cf. Jacques Kohn, Orgue et bima, op. cit. |

| 26 | Cf. Heymann Claude, Vie communautaire, spiritualité et musique dans la campagne alsacienne. Le rôle des chantres, Archives juives 2002/1 – N° 35, p. 133. |

| 27 | Jean Jonathan Rosen, Max (Moché) ROSENZWEIG 1902 – 1977, Director of the synagogue choir of Metz between 1934 and 1967, http://judaisme.sdv.fr/histoire/rabbins/hazanim/rosenzw.htm |

| 28 | CD recorded by Albert Kirch, track 12. |