by Hervé Roten

Traditionally attributed to King David, the 150 poetic texts that make up the book of Psalms, however, have a more uncertain origin: it would probably be a set of poems written during the 4 to 5 centuries that followed the reign of David [1]The writing of the Psalms would be between – about 1000 and – 538 which marks the end of the Babylonian exile. It is impossible to give a precise dating of the psalms taken individually. … Continue reading.

Originally, the Hebrew Bible gives no specific denomination for this compilation of 150 psalms of 2,527 verses. But later rabbinical literature will qualify this set of Sefer Tehilim which literally means “Book of Praise“.

The generally accepted name today of “Book of Psalms” comes from a literal translation of the Greek Biblios Psalmôn and Latin Liber Psalmorum. In Greek Psalmos means an air played on a stringed instrument called psaltery, of the organological family of zithers. According to André Chouraqui, these translations “gave the contents of the collection [of Psalms (Editor’s Note)] a name evoking the way in which its elements can be sung, rather than the very nature of these. in Hebrew, Tehilîm, is a word derived from the root hll, praise … to designate poems for the praise of Yahweh »[2]CHOURAQUI André, La Bible, Ed. Desclée de Brouwer, 1989, p. 1115..

Note that the numbering of the psalms is not the same in the Septuagint [3]First translation of the Bible in Greek, probably in the third century BC and in the Vulgate [4]Translation of the Bible in Latin by St. Jerome and adopted by the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century. that in the Masoretic text, even if it leads to the same total of 150 psalms.

Psalms and chanting in the Temples

As André Chouraqui points out, one can not conceive the psalms without the music that accompanies them. At the time of the First and Second Temples, music played an important role in the worship process [5]Cf. the many descriptions of Temple worship in the historical books of the Bible (Chronicles I and II, Ezra, Nehemiah).

In the first century after Christ, the Mishnah [6]The Mishnah is a collection of sentences and legislation of Talmudic elders called tanaim. describes the Temple Orchestra as consisting of a minimum of 12 instruments, mainly stringed (2 nevelim, 9 kinnorot and 1 mesiltayim) to which are added 12 singers (Mishnah, Arakin, II, 3-6).

The musical part of the cult, vocal and instrumental, is traditionally linked to the offering of sacrifices. And the psalms are widely represented (psalms of thanksgiving or penitential). Many psalms thus invite the faithful to sing the Lord (Ps 33, 66, 81, 84, 92, 95, 96, 98, etc.).

The bipartite or tripartite division of the verse in Biblical poetry also suggests in the musical performance the use of the antiphonal form (alternation of two choruses) and responsorial (response of the faithful to the High Priest). The participation of the people in worship, or the alternate performance of two choruses, seems implied by the use of brief refrains, as in Psalm 136, and by other clues (Halleluyah, Amen, etc.).

Some beginnings of psalms contain musical indications whose meaning remains sometimes mysterious: thus the incipit of Psalm 6, Lamenatseah ‘al ha-sheminit literally means “To the leader of the singers on the eighth”. Does this “eighth” designate an eight-string instrument or does it indicate that the piece is sung in the eighth mode? Is the melody doubled to the octave as some daring translations would imply? In the psalms, we find many words that are literally untranslatable, and which may contain musical indications; according to musicologist Israel Adler, “the obscure term selah ‘ seems to indicate the precise place of an” entry “(instrumental interlude? choral response?)”, however, disputed by some researchers.

The vocal and instrumental music of the psalms that resonated in the Temples died out with their destruction. And no one can seriously claim today to find what it looked like, for lack of musical notation! But, the vocalized reading of psalms, the psalmody, was transmitted through the synagogical institution.

Psalms and psalmodies in the synagogue

The synagogue actually coexisted for almost five centuries alongside the Temple but the worship that took place there was certainly very different from the latter. Indeed, the synagogue is not a temple, but usually the place where men gather to listen to the reading of the Torah. The worship which developed there is in this reading, point of departure of comments, and in the singing of psalms, completed by prayers said in common.

Later, from the Talmudic period, the number of psalms used in public worship, domestic ceremonies or other occasions has grown, largely responding to popular demand. The traditional prayer book now contains seventy complete psalms and nearly two hundred verses of the psalter have been introduced in different liturgical passages.

These psalms are recited in a particular way called psalmody. The psalmody, like the biblical cantillation, is generally governed by the principle of the dichotomy: each sentence is formed of two parts separated by disjunctive accents, the strongest of which is at the end. This punctuation, both textual and musical, is expressed melodically by a syllabic cantillation, generally around one, two or three notes, interrupted by a cadence, sometimes melismatic. As noted by the musicologist Israel Adler (1968, 475), “this process is reminiscent of the use of the recitation string in the plainchant of the Church.”

Another characteristic feature of cantillation or psalmody is the use of predetermined melodic formulas within a mode, whose main role is to regulate the declamation of the text. There are thus initial and terminal formulas, connective and disjunctive. This type of modality is still found today in all Jewish communities, which attests its degree of antiquity.

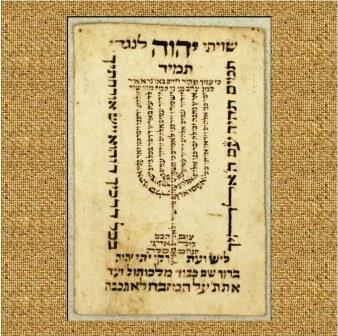

The musical notation of the psalms

Until about the beginning of the 19th century, the psalms were always transmitted orally. It is only two centuries since we began to transcribe their music. However, above the Hebrew text of the psalms, we find the presence of small graphic signs: te’amim or biblical accents, whose system was developed between the 6th and 9th centuries of the Christian era.

The te’amim are small graphical signs, placed on or below words, which indicate the place of the tonic accent and allow to separate or link the words. There are connective te’amim (called servants) and other disjunctives (called kings). The two main disjunctives te’amim are Sof pasuq and Etnah’ta; they correspond substantially to the point and the comma.

In troubled times where oral tradition is weakened, te’amim systems offer synagogue servants an effective mnemonic device for cutting and reciting biblical texts without any punctuation. Signs of emphasis and interpunctuation, the te’amim do not indicate notes, intervals or even modes, but melodic formulas whose outline depends on the choice of mode. Thus the same succession of te’amim is sung differently if it applies to the mode of the Pentateuch, that of the Prophets or even that of the scroll of Esther.

The development of the system of te’amim lasted nearly three centuries. Several notations coexisted at first. But finally, it is the system codified in the tenth century by Aaron ben Asher in Tiberias – and called for this “Tiberian system”, which prevailed in virtually all Jewish communities. However because of its complexity – it included no less than 29 different signs! – it was not rigorously applied everywhere. Therefore, despite the role played by te’amim in the maintenance of musical traditions, the biblical cantillation of the same text varies more or less from one community to another. The melodies undeniably all have a “family resemblance” which indicates a common origin; but with time and the mutations that accompany it, melodic differences, sometimes important, have appeared.

Henceforth, there is no single music of the psalms inside Judaism, but almost as much music as there are traditions and currents in Judaism.

Psalms: meeting point between Jews, Catholics and Protestants

But if the psalms have reached such a reputation in the Judeo-Christian world, it is because Christians and Jews share the same founding texts: the first assemblies of Christians, largely composed of Jews, continued to pray at the synagogue and thus transposed part of the synagogue liturgy into the new cult. The psalms, like other prayers became one of the pillars of the Catholic liturgy and later, in the sixteenth century, Protestant liturgy.

As it is a poetic work with particularly lyrical accents, the psalms have been an intense source of inspiration for many composers, be they Jews such as Salomone Rossi (around 1570-around 1630), Catholics such as Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594), or Protestants (Loys Bourgeois, Clément Janequin, Claude Le Jeune, Claude Goudimel and Pascal de l’Estocart).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

– ADLER Israël, La pratique musicale savante dans quelques communautés juives en Europe aux XVIIème et XVIIIème siècles, Paris – La Haye, Mouton & Co, 1966, 2 vol.

– AVENARY, Hanoch, “Music”, Encyclopaedia Judaïca, vol. 12, Jerusalem, Keter Publishing House, 1972, pp. 566-664.

– CHOURAQUI André, La Bible, Ed. Desclée de Brouwer, 1989, pp. 1115-1232.

– « Psaumes, Livre des », Dictionnaire encyclopédique du judaïsme, coll. Bouquins, éd. Cerf/Robert Laffont, 1996, pp. 831-832.

– ROTEN Hervé

– Les traditions musicales judéo-portugaises en France, Paris, Maisonneuve &Larose, avril 2000, 282 p.

– Musiques liturgiques juives : parcours et escales, Coll. Musiques du monde, Cité de la Musique / Actes Sud, 1998, 167 p.

Listen to the playlist : The Psalms: about psalms 92 and 93

| 1 | The writing of the Psalms would be between – about 1000 and – 538 which marks the end of the Babylonian exile. It is impossible to give a precise dating of the psalms taken individually. Only Psalm 137, as it refers to the Babylonian exile, obeys precise criteria which make it possible to date its composition to the postexilic period. |

|---|---|

| 2 | CHOURAQUI André, La Bible, Ed. Desclée de Brouwer, 1989, p. 1115. |

| 3 | First translation of the Bible in Greek, probably in the third century BC |

| 4 | Translation of the Bible in Latin by St. Jerome and adopted by the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century. |

| 5 | Cf. the many descriptions of Temple worship in the historical books of the Bible (Chronicles I and II, Ezra, Nehemiah) |

| 6 | The Mishnah is a collection of sentences and legislation of Talmudic elders called tanaim. |