by Hervé Roten

Salomone Rossi, or Shlomo Mi-ha-Adumim in Hebrew, came from an old Jewish family in Mantua, where he was born around 1570. Profiting from the tolerance granted to the Jews by the Dukes of Mantua, he grew up in a relative tranquility. The city’s Jewish community of about 2,300 people had nine synagogues and twenty-four rabbis. It is in this particularly favorable context that the young Rossi learned art music.

At the time, the spirit of openness of the Renaissance encouraged an enlightened audience of Jewish amateurs to open up to the musical practices of their time. This explain the existence of music and dance schools in Venice in the first half of the fifteenth century. At the end of this same century, Jewish composers and musicians like Giuseppe Ebreo and Guglielmo Ebreo emerged. Note that the term “Ebreo” added to the name of the composer – probably by order of the censor – allowed to formally identify the Jewish origin of these two musicians; this designation was applied to all Italian Jewish composers of this period.

During the sixteenth century and until the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Court of Gonzaga from Mantua hosted many Jewish musicians. Called “el Ebreo del Mantova” (the Mantua Jew), Salomone Rossi appeared for the first time in the registers of the court of Mantua in 1587, first as a chorister, then as a viola player, and finally as composer. His first compositions, a book of Canzonette with three voices (1589) and a book of madrigals with 5 voices (1600) are dedicated to the duke Vicenzo Gonzague. In return, the latter exempted in 1606 the wearing of clothing signs marking as Jews. In spite of this relative integration, Rossi will never denied his belonging to Judaism.

For over forty years, Salomone Rossi remained in the service of Dukes Vicenzo and Fernando Gonzaga. From 1590 to 1612 he worked alongside with Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), the brilliant creator of Orfeo. His madrigals, however, did not feel the influence of the latter. In 1630, Mantua was besieged and ransacked by Austrian troops. Most Jews were then forced to flee the city. At this moment all traces of Rossi were lost; we suppose he died soon after, perhaps of the plague.

During his lifetime, his compositions were the subject of twenty-five publications. His work is impressive: nearly three hundred pieces, mainly vocal (canzonettes, duets, trios and madrigals on poems by Italian authors of the time) but also instrumental where he contributes to the development of the violonistic style and the development of the baroque sonata.

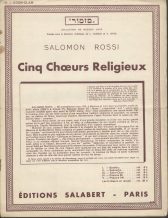

The Jewish works of Rossi were published in a two-volume collection, printed in Venice in 1622-23 under the title of Hashirim asher lish’lomo (Songs of Solomon), and containing thirty-three Hebrew sacred songs for chorus of three to eight voices. The title of this collection has often been misleading: no text comes from the Song of Songs attributed to King Solomon, the collection being composed of twenty psalms and a dozen hymns or songs, the Solomon of the title therefore refers to Salamone Rossi himself.

The interest of these choruses – in addition to their undeniable beauty – lies in the fact that they constitute one of the first attempts at introducing polyphonic art music into synagogical worship. They also bear witness to the reforming ideas that are shaking up the Italian communities. These ideas are mainly supported by a curious character, Rabbi Leon of Modena (1571-1648).

The latter, a true “jack-of-all-trades” (he claimed to have practiced no less than twenty-six different jobs throughout his career!) introduced in 1605 to the synagogue of the community of Ferrara a choral practice on the occasion of some Shabbos services and holidays. Throughout his life, he defended the idea of the necessary renewal of synagogue music that seemed out of date to him. Thus, of course, he prefaced the first edition of Solomon’s Songs in 1622-23 to claim the entrance in the synagogue of the musical language of his contemporaries.

This reformist current, however, did not succeed in imposing itself on all the Italian synagogues, and the Solomon’s songs were probably performed there only a limited number of times. One must say that the musical language used by Rossi completely ignores the traditions of synagogical music and its cantillations. Rossi applied to Hebrew texts the melodic language developed for half a century in Venice. It therefore often remained below Monteverdi innovations and rather reminded of his contemporaries Lassus or Viadana.

It was not until the nineteenth century, and the musicological work of the singer Samuel Naumbourg (1815-1880) in collaboration with Vincent d’Indy (1851-1931) then twenty-five years old, so that the synagogal work of Salomone Rossi returned finally to the repertoire of French and foreign synagogues.

Look at our archives about Salomone Rossi