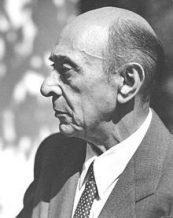

Arnold Schönberg – or Schoenberg – was a Jewish Austrian composer, music theorist, and painter. Born on September 13, 1874 in Vienna, he died on July 13, 1951 in Los Angeles.

Arnold Schoenberg was born into a lower middle-class Jewish family in the Leopoldstadt district. His father Samuel, a native of Bratislava, was a shopkeeper, and his mother Pauline was native of Prague. Arnold was largely self-taught. He took only counterpoint lessons with the composer Alexander Zemlinsky. He was leader of the Second Viennese School, before setting down in Berlin to teach music. A world-known pedagogue and music theorist, he taught students such as Hanns Eisler, Egon Wellesz, Otto Klemperer, Theodor Adorno, Viktor Ullmann, Winfried Zillig, Max Deutsch, René Leibowitz, Nikos Skalkottas, Josef Rufer, Roberto Gerhard and John Cage.

Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name serialism by René Leibowitz and Humphrey Searle in 1947. This technique was taken up by many of his students, who constituted the Second Viennese School.

In the early 1920s, he worked at evolving a means of order that would make his musical texture simpler and clearer. This resulted in the “method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with one another” (Schoenberg 1984, 218), in which the twelve pitches of the octave are regarded as equal, and no one note or tonality is given the emphasis it occupied in classical harmony.

SCHONBERG AND JUDAISM

Excerpt from the article from Milken Archive of Jewish Music

Little is known about Schoenberg’s religious upbringing or childhood Jewish experiences. What might seem to be major milestones in his life—his conversion to Protestant Christianity in 1898 and, especially, his return to Judaism—are in fact only events in a continual internal struggle and spiritual quest. His conversion to Christianity, however, was not (as the distinguished music scholar Alexander Ringer observes in his well-known study, Arnold Schoenberg: The Composer As Jew) “under secularizing or assimilationist influences, but rather because, virtually untutored in Jewish values, he looked for other vessels to quench his spiritual thirst.” By 1923, he was already committed to Jewish national concerns, and his drama Der Biblische Weg (The Way to the Bible; 1923–27) advocated a temporary national home for the Jewish people prior to eventual permanent settlement in Palestine.

Schoenberg formally converted back to Judaism in 1933, but he considered it the culmination of maturation, spiritual development, and fulfillment of personal destiny, and he claimed that he had always considered himself a Jew. The dominant theme throughout his life derives from a dualistic outlook on all phenomena as interactions or relationships between the concrete and the abstract, usually expressed as an irresolvable conflict. He seems to have sought resolution of that conflict—between an amorphous “God awareness” and a hunger for structure—in formal religion.

During the last two decades of Schoenberg’s life, Jewish subjects became increasingly important to him. Between 1930 and 1932 he worked at his opera Moses und Aron, which occupies a central position in his oeuvre. In 1938, the year in which the Kristallnacht pogroms signaled the end of Central European Jewry, he composed an English setting of the kol nidrei recitation; and, in 1947, he wrote A Survivor from Warsaw, which Ringer calls the “ultimate artistic expression of both Schoenberg’s lifelong Jewish trauma and his abiding faith.” The 1950 choral setting of Psalm 130 in the original Hebrew, his contribution to an Anthology of Jewish Music, was dedicated to the State of Israel. But Schoenberg was never able to complete any of his large-scale religious works, including Moses und Aron and an oratorio Die Jakobsleiter (1917–22). Each breaks off with the protagonist left unable to find fulfillment through prayer.

Look at our archives about Arnold Schönberg