Born on July 24, 1932, in Algiers among a family of musicians – his father Charles was director of a music school – Jean-Claude Sillamy was acquainted with all the works of the great composers since he was very young.

At the age of nine, he conducted a small symphonic orchestra. Student, aged of 10, in an advanced class of solfeggio in Algiers’ music conservatory, he started to study harmony and received a first prize award for music composition with a work for string quartet.

Later on, interested by this young and talented musician, a patron gave him the means of continuing his studies in Paris. This is how he entered the National Music School of Paris, in the counterpoint and fugue class led by Noël Gallon.

At the same time, he worked for three years in the École Normale de Musique de Paris, under the direction of Alice Pelliot, former teacher of Darius Milhaud and Arthur Honegger. He also worked on harmony and choral singing at the Gregorian Institute under the direction of Edouard Souberbielle.

During this period, he also finished his university studies (he is graduate of university, in psychology), and started visiting Jewish spheres, in particular Gilbert-Bloch d’Orsay school. Very interested by this Jewish studies center, he started to develop biblical studies. What impressed Jean-Claude Sillamy most were the traditional chants performed by Jewish students originaly from various communities : North Africa, Eastern and Central Europe, Asia…

During this period, he also finished his university studies (he is graduate of university, in psychology), and started visiting Jewish spheres, in particular Gilbert-Bloch d’Orsay school. Very interested by this Jewish studies center, he started to develop biblical studies. What impressed Jean-Claude Sillamy most were the traditional chants performed by Jewish students originaly from various communities : North Africa, Eastern and Central Europe, Asia…

He became curious by those strange signs above the biblical text. He had the feeling it was an old musical notation, allowing to restore this music from Antiquity that was supposedly lost forever. He suspected that these traditional chants were notated, black on white in antique musical signs, above or under the text of the Bible. This discovery shocked him. The Bible would thus be a sung and notated document? One would just decipher and perform these hieroglyphs, called in Hebrew « Taamim » (Taam in singular).

Equipped with a tape recorder, he went to several countries, recording liturgical chants of many Jewish communities, sung following the Taamim. He spent several years doing this work of studying his recordings. The tapes are deposited at the Phonothèque Nationale de Paris, as well as in Jerusalem’s University, in the musicology department, led then by Israel Adler.

Comparing the melodies, in order to find the original melody, he formulated the theory that the precise scales are at the start of the many melodies. He presented, step by step the history of the music of the Hebrew people, enlightened by the data from the Bible, visiting the greatest museums in order to find the ancient instruments which might have been used to perform such music, one described by the Bible « tender and soft ».

The study of the Hebrew Taamim revealed to him an extremely elaborate musical technique from the times of the first Kings of Israel, which consisted in establishing a musical scale serving one function to another. If the first scale is austere and diatonic, the second, built from the first, is chromatic and colored. Several rules would thus be at the head of the birth of fundamental and complementary music scales.

Thus, opposed to the common opinion about the birth of polyphony in the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages, Jean-Claude Sillamy came to the conclusion that polyphony was largely used in the Great Temple of Jerusalem, in particular at the time of King David. That harmony is totally different from our Western harmony, based on thirds and the function of tension-rest – dominant-tonic.

For him, all the music of the world, and moreover non-tempered music, possessed virtually in themselves their proper harmonies. Trying to restore this musical and harmonic language from the Antiquity, adapting it to our Western tempered system, Jean-Claude Sillamy composed an entirely original music.

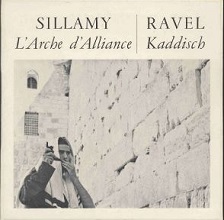

From this work, Jean-Claude Sillamy dedicated himself to give a new rise and new expression to Jewish singing. He published several books and studies dedicated to Jewish music (Essai de reconstitution de la musique de la Bible, 1957 ; La musique dans l’ancien Orient (2 tomes), 1986 ; La musique des communautés juives d’Afrique du Nord, 1987 ; a study on Le principe de la modulation dans le fragment babylonien d’Ur : U.7/80 (XVIIIème siècle av. J.C.) (from a non-identified instrument of the time : the « gis za mi »)).

Surrounded by his loved ones, he passed away on July 29, 2016 in Ajaccio.

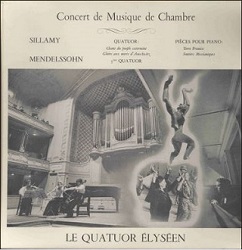

His archives, given to the European Institute of Jewish Music in November 2016 by his widow Lina Sillamy, gather around 80 documents (discs, field recordings, articles, books, photos…) unfindable for most of them.

Read the article about the Sillamy collection

Browse documents from the Sillamy collection