Israeli Singer and collector of Jewish Yemenite music.

Bracha Zefira was born in Jerusalem in 1910. Her father emmigrated from Yemen in 1887, and settled in the then Yemenite neighborhood of Nahalat Tsvi, in Jerusalem, and married Na’ama Amrani, Bracha Zefira’s mother. Zefira’s mother died while giving birth to her, and her father died from typhus when she was three years old. After the death of her parents, she was brought to live with her uncle in Jerusalem, but fled from his house at the age of five and was placed with a family in the Bukharan Quarter of Jerusalem. This area of the city was inhabited by immigrants from Bukhara, Tashkent, Samarkand, and Persia. After three years, her adopted family left the city, and Brakha was placed with a widow in the Yemin Moshe neighborhood in Jerusalem, where most of the residents were Sephardic Jews from Salonika.

As she moved from one neighborhood to the next, Bracha was attracted to the songs she heard. The synagogue played a central role in the lives of the families she grew up with, and in them, she was exposed to the melodies of the liturgy, absorbing piyutim and more. Like many girls of Sephardic families, Zefira attended a school in the old city, and later the Lemel School. On her walks through the old city of Jerusalem, she and her friends were exposed to Arabic songs and melodies. They used to challenge themselves by attempting to adapt the words of Hebrew poems, especially those of Bialik, to the Arabic or Sephardic melodies that they liked. Later on in her life, Bracha employed this technique of text adaptation extensively.

Her success in Shefeyah motivated her teachers to send Zefira to additional music studies. She moved to Jerusalem in order to study at the Kedma School, directed at the time by Sidney Siel. After several months, she left the school, as her teachers at Kedma recommended that she should study acting instead. She moved to Tel Aviv and was accepted to the Palestine Theater, founded by Menehem Gnessin, as well as to his acting school. The theater was closed the same year, in 1927, and Zefira joined the satirical theater Hakumkum, where she performed until 1929. While performing with Hakumkum, she also appeared as a solo singer and as a choir conductor on various occasions. The Russian director Alexander Diki saw her in one of Hakumkum’s shows and recommended her to go study in Berlin. Eventually she went there, with the help of Meir Dizzengof, among others, and studied acting and music at the studio of Max Reinhardt.

Bracha Zefira and Nahum Nardi

It was in Berlin, in 1929, where Zefira had perhaps the most important encounter of her musical career, when she met pianist and composer Nahum Nardi. In regards to their meeting, she relates, “That very evening … I begged him to sit at the piano and play the songs I would sing to him, and try to improvise an accompaniment. I sang Bialik’s “Yesh Li Gan” and “Bein Nahar Prat” for him, and Sephardic piyyutim … and other songs that I was used to singing from Shefeyah. He was a quick learner, had an excellent ear and a light touch at the piano, and was familiar with Hebrew lyrics, although from a traditional galut (Diaspora) perspective. His playing and the simple harmonies electrified me. I felt that the song had taken on new sounds …”

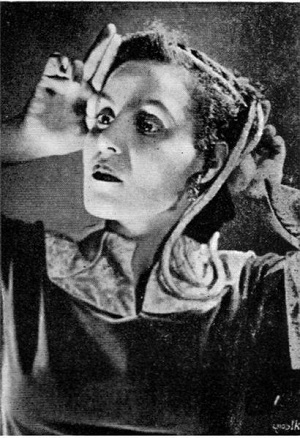

That same year, Zefira and Nardi began a series of concerts in Germany and other parts of Europe, and Zefira left her acting career to dedicate herself to singing. Their tour’s program included songs of different oriental ethnic groups that Zefira knew from her childhood including Sephardic songs, Jewish songs from Yemen, Persia, and Bukhara, as well as songs of Bedouins and Palestinian Arabs, all arranged by Nardi. Zefira added theatrical gestures to their performances, which were favorably commented upon by critics. She performed in front of some important figures, such as Albert Einstein and Russian director Sergei Eisenstein.

In order to find musical material, Bracha returned to the neighborhoods she grew up in. She asked old women to sing her their songs, and she participated in local festivities. She was also helped by experts such as Yehiel Adaki who taught her songs of the Yemenite tradition, and Yitzhak Eliyahu Navon, who taught her songs from his wide Sephardic repertoire, in return for her accompanying him on his walks. According to Emanuel Yerimi, their success in Palestine was also due to the demand for Hebrew singing, and to the relatively small amount of artists working in the field.

Following two years of collaboration, Zefira and Nardi were married, and in 1931 their daughter Na’ama, who became an opera singer, was born. The duo kept expanding their repertoire, adding Egyptian, Ethiopian and Turkish songs, spiritual songs from the U.S., and more. In 1931, they went on tour of Alexandria and Cairo, which was critically acclaimed, followed by a similar tour in 1936. One of their most important performances was at the premier broadcast of the Palestine Broadcasting Service in 1936, which was the first radio broadcast in Hebrew. In 1937 they embarked on a tour in the U.S., where they recorded three albums for Columbia Records, which according to Natan Shahar, “served as a calling card of sorts for the nascent field of Hebrew song in Palestine”

After her separation from Nardi, Zefira turned to other composers, each of them interested in a specific genre. Paul Ben-Haim (who frequently accompanied her on piano) was interested in Sephardic songs, Oedeon Partos in Yemenite and more complex songs, and Marc Lavry preferred songs with a light and danceable style. Other composers she worked with were Boskovich, Mahler Kelkshtein, and younger composers, like Noam Sheriff, Hanoch Ya’akovi, and Ben-Zion Orgad.

In order to perform on the same big stages in Israel, Zefira had to continue refreshing her repertoire. She continuously collected new songs from various ethnic groups in Palestine. Although she could read musical notation, she could not write it. Hence, she tried to convince the composers to come with her to hear the source, but they preferred that Zefira sing the songs for them.

One peak in Zefira’s career was a concert with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (later the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) in 1939, conducted by Marc Lavry, where she performed songs of Nardi, Ben-Haim, and Lavry. At the time, there were still local critics decrying orchestral music with oriental origins, speaking against the idea of an oriental singer accompanied by an orchestra. In the following years there were debates and discussions on this subject, and eventually the musical atmosphere became more approving of this new style. In 1939 Zefira changed the form of her usual musical accompaniment. She organized an instrumental ensemble comprised of members of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra who accompanied her in many concerts; however, she continued to perform while accompanied by piano, usually played by Paul Ben-Haim.

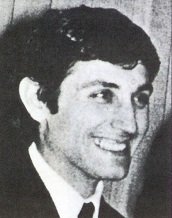

In 1940 Zefira met Ben-Ami Zilber, a violinist in the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. They were married, and in 1943 had a son, Ariel Zilber, who became an important figure in the Israeli rock scene during the seventies. After a year-long break due to Ariel’s birth in 1943, Zefira continued to perform, giving many concerts until 1947, which were usually acclaimed by critics. In 1948 she went on a successful tour of Europe and the U.S. that lasted two and a half years. During the tour, she performed, among other places, in refugee camps in Germany. A special event on the tour was the visit of Egyptian poet Dr. Ahmad Zaki at one of her shows in New York. He invited friends, and one of them later wrote an article in an Arabic newspaper about her show. Considering the relations between Israel and Egypt at that time, an Arabic article acclaiming an Israel artist was an unusual event.

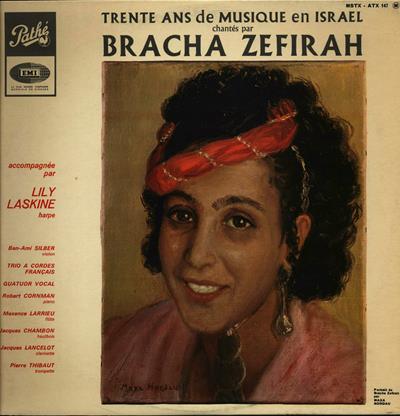

Zefira’s turn to art music, rather than the Israeli folksong, was acclaimed by some, while criticized by others. While some were impressed by her effort to “elevate” traditional tunes to the level of art music, others were sorry for her leaving the field of Zemer Ivri that arguably suited her more naturally. She herself wrote in her book Kolot Rabim that only a few of the hundred of songs that were arranged for her had become true assets. In 1966 she received the Engel Prize, for “inserting the oriental melody into Israeli music, symphonic and folkloric, through 30 years of her shows in Israel and abroad.”

During the 1950s public interest in Zefira declined. According to Emanuel Yerimi, the Israeli audience had become accustomed to her old style which had once been innovative, while her new, more artistic, style was less favored.

During this period she again went abroad, and returned in 1957, where she continued to perform occasionally. She also studied drawing, in Israel and later in Paris, and had some exhibitions. During the sixties she continued to perform on occasion, and her last show was in the mid seventies, at the Tel Aviv Museum. In those days the demand for her shows was quite limited.

Her husband Ben Ami Zilber died in 1984, and that deeply affected her, as well as her daughter’s death in 1989.

Brakha Tzefira died in 1990. Her death was not mentioned in the news or on the radio, but the weekend newspapers wrote about it. The city of Jerusalem named a street after her.

Despite her success in Palestine, Zefira experienced some difficulties due to racism. One incident occurred upon her first performance in Tel Aviv, which was supposed to be in Ohel Shem hall, but the management refused to let her perform due to her Yemenite origin. Thanks to public criticism, the incident was amended, and Zefira was allowed to perform there.

Another incident unrelated to her ethnicity, but rather to ideological motives of promoting the Hebrew language, occurred in 1939, when the council of Tel Aviv cancelled her concert in Ohel Shem, due to the fact that it contained songs that were not in Hebrew.

Zefira’s Repertoire

According to Zefira, her repertoire included over 400 songs, many of which she helped create, either by working with composers on the melodies, or with poets on the lyrics. Her songs based on Arab or Bedouin melodies include Ben Nahar Prat, Yesh Li Gan, Lamidbar, Aley Giv’a, and were arranged by Nardi. She sang Piyyutim of Yemenite and Sephardic Jews with their original words, like S’I Yona, and Hamavdil. For Sephardic Romances she either replaced or translated the Ladino words, like Hitrag’ot with words by Yehuda Karni.

Thanks to Zefira, melodies of various communities were adapted into Hebrew songs, like Bukharan (Ets Harimon) or Persian (Mahol Parsi). Additionally, Zefira would sing folk songs in their original language, like Ladino, and songs containing original music by various contemporary composers.

Zefira was a pioneer of singers from oriental origin who studied the European vocal technique; her followers indluded Naomi Tsuri and Hanna Ahroni.

Biography written by the Jewish Music Research Center in Jerusalem.

Listen to the playlist dedicated to Bracha Zefira’s songs

Read the biography of Nahum Nardi